Recently, Trump’s Asia trip has once again rekindled attention on rare earths: first he signed yet another “framework agreement” with Japan, boasting about supply‑chain alternatives. Then after meeting with Chinese officials he couldn’t wait to announce that China would suspend rare‑earth controls — supply chains are still needed. Back in Washington, Bessent swore up and down that China’s control of rare earths “will be broken within two years.”

Such rapid flip‑flopping brought to my mind that familiar line from a Spring Festival sketch in Tangshan dialect: “Are they cutting or are they补?” Behind this is a reflection of America’s current dysfunction in self‑correction, a loss of direction that forces it to pander to a kind of “cult of winning” and delude itself with slogans. While the U.S. continues to paint lofty technological promises for its industries, objective realities are brewing punishments and reckonings. And all of this can be summed up in one familiar diagnosis:

It’s a systemic problem!

Trump 2.0: fighting for rare earths just to “win”

The newly inaugurated Trump 2.0 administration is desperate on rare‑earths, grabbing anything that moves — like the character Lian Erye in Dream of the Red Chamber, “bringing everything, fragrant or foul, into the house”:

In February, while Bessent was extorting a mineral deal with Ukraine, Trump told the media he had “won $500 billion in Ukrainian rare earths,” ignoring the sober facts already published by S&P and the US Geological Survey — Ukraine lacks precise exploration and commercial prospects and is not a major rare‑earth country.

It’s not a secret: the USGS annually lists countries with significant rare‑earth holdings, and Ukraine is not among them. Anyone can see this, let alone the U.S. president.

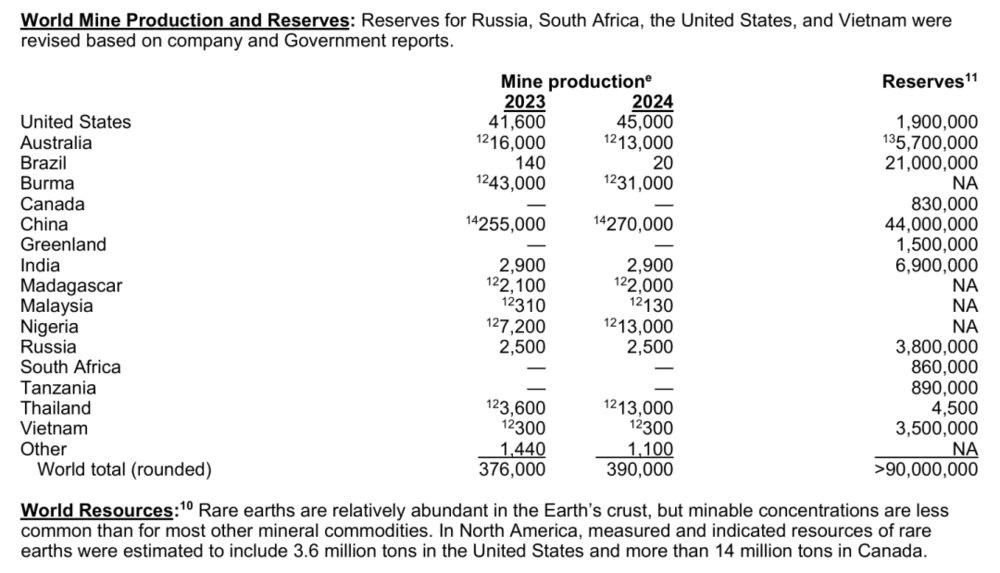

The 2025 Mineral Commodity Summary showed no Ukraine among major rare‑earth resource holders or producers. This is public information. Source: USGS.

In September, the Pakistani prime minister visited the U.S. and displayed a so‑called “rare‑earth treasure box,” along with a $500 million exploration cooperation plan taken away from the Oval Office. Again, Trump ignored the USGS data and was later shown to be wrong: the “treasure box” did not contain rare earths, and much of the claimed mining area was in conflict‑prone Punjab.

Throughout this, Greenland also appeared in negotiations — beyond equity talks, Trump even shouted about annexing Greenland — even while U.S. think tanks were warning him that Greenland’s estimated projects would take 10–15 years at best to come online, and that’s just for mining.

A somewhat more plausible partner was Australia: Trump and Prime Minister Albanese signed deals worth over $8 billion, vowing to rebuild supply chains; Lynas promised breakthroughs on heavy rare earth technology. Yet Australia’s production has largely shifted to Southeast Asia — domestic reserves exist but extraction and processing capacities are limited.

In short, three quarters into his term, Trump’s economic warfare playbook includes tariffs, courting investment, and rare earths — all seemingly aimed at one word:

Win!

Even if it’s just rhetoric to placate MAGA voters.

A decade‑plus of U.S. laws and policies

To be fair, America’s obsession with replacing rare‑earth imports isn’t just a Trump 2.0 improvisation. The U.S. has been talking about breaking this dependence for over 15 years. So let’s briefly recap the last 15 years of U.S. rare‑earth policy — this isn’t some social‑media novelty this year, it’s history repeating itself.

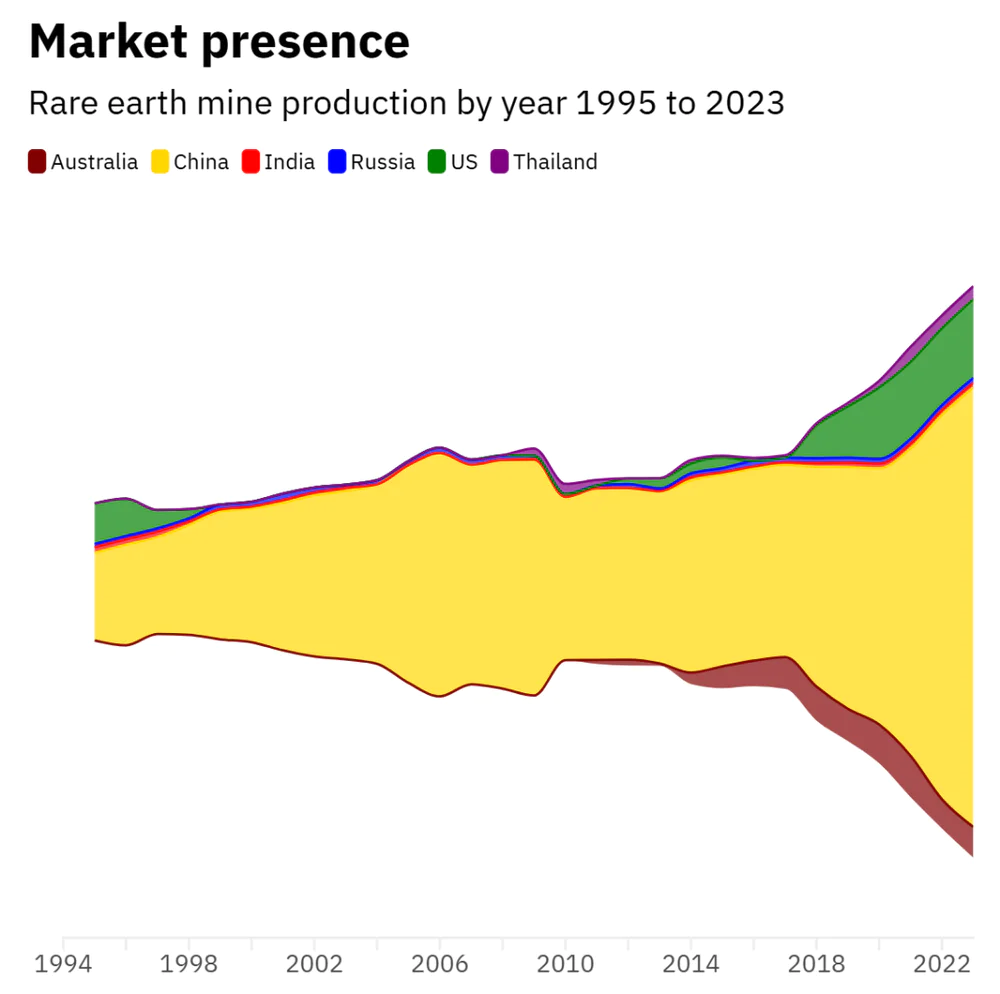

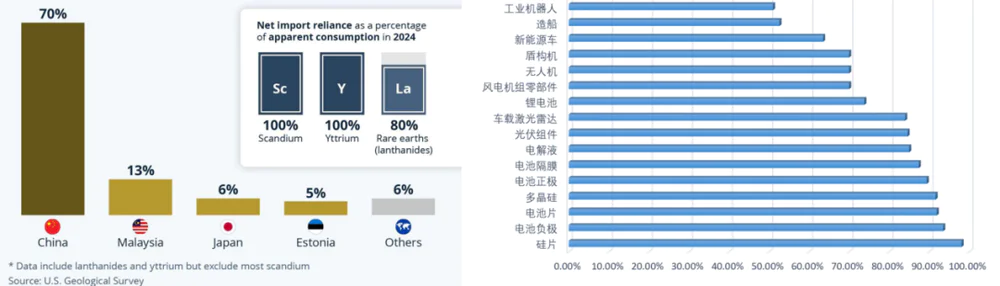

Go back to 2010. At that time the West was collectively confronting China — then accusing Chinese rare‑earth production of environmental pollution, whereas today they accuse Chinese export controls of threatening supply‑chain security. In August that year, the U.S. Congressional Research Service reported that the U.S. had shifted from self‑sufficiency in rare earths to 100% import reliance over 15 years, and that China’s dominant role raised “serious concerns.”

From that moment policymakers treated rare earth supply as a national‑security and strategic issue, seeing rare earths as a tool in geopolitical competition. Then–Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared that the U.S. and its allies should reduce dependence on Chinese rare‑earth production.

This kicked off a flurry of legislation: in 2010 the U.S. revived acts on rare‑earth supply and processing, aiming to rebuild competitive domestic sectors for mining, processing, refining, metal production, alloys, and magnet manufacture, and to establish stockpiles. The next year Congress passed the Critical Minerals Policy Act and the Rare Earths and Critical Materials Revitalization Act, mandating resource assessments, streamlined permitting, R&D support, loan guarantees, and more. Departments including the Interior and Defense were authorized to assess uses of elements and develop contingency plans.

During Trump’s first term he arguably pushed harder on rare earths than his predecessor, issuing operational executive orders. In 2017 he signed orders to assess and strengthen manufacturing and defense industrial base resilience and to secure reliable supplies of critical minerals. The USGS issued a major report (Professional Paper 1802) listing 23 critical minerals vital for national security and economic welfare — the first such update in 44 years.

In 2018 and 2019, multiple federal reports and lists highlighted rare earths among 35 critical minerals and proposed concrete actions and recommendations. So it’s unfair to say that prior to 2020 the U.S. only mouthed slogans — they put actual programs and institutional structures in place. Trump’s first term built a framework intended to change U.S. reliance on foreign sources; that helped enable later actions. So while his team had its “amateur hour” aspects, it also contained elements of reform that mattered.

And yet, as described above, after preparing for years the U.S. still fumbled when responding to China’s countermeasures. Trump’s first‑term push on rare earths makes his second‑term posture — sometimes untethered to facts — all the more curious.

2020 was another turning point: the Trump administration for the first time invoked the Cold‑War era Defense Production Act and allocated $250 million toward rare‑earth supply chains, directing funds to specific companies and projects to accelerate mining, separation, processing, and magnet manufacture — a signal intent to break dependence on China.

Biden continued and deepened this strategy. In February 2021 he signed Executive Order 14017, ordering a comprehensive review of supply chains including rare earths and prioritizing action. The White House then released a 100‑day assessment advocating revitalization of the critical minerals and materials industry. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act committed $1.2 trillion overall, explicitly naming rare earths in the clean‑energy supply chain. Biden also expanded the Defense Production Act coverage to include Canada, Australia, and the UK as “domestic sources” to ease investment.

From this retrospective, regardless of implementation gaps, U.S. rare‑earth replacement has become a continuous policy line across administrations. It’s now a long‑term national strategy: the Defense Department’s slogan this year is “from mine to magnet” — the U.S. wants the whole chain.

And the deadline is 2027 — likely the basis for Bessent’s “break China in two years” claim.

Not zero progress — a “zero breakthrough” after 15 years

Over 15 years the U.S. has made some gains, most touted is the reopening of the Mountain Pass rare‑earth mine in California. Once in its heyday it supplied 70% of the world’s rare earths before closing in 2002 after a toxic spill. Reopened due to renewed government focus, it’s now the only large producing U.S. rare‑earth mine; in 2024 it produced 45,000 tonnes, making the U.S. the world’s second‑largest rare‑earth producer by volume. That’s touted as the foundation for rebuilding the domestic industry.

Theoretically the U.S. has decent natural endowments: domestic resources are rich; even coal ash and other byproducts could hold up to 11 million tonnes of rare earths, about eight times currently estimated domestic reserves.

On processing, the U.S. has some progress. Investments are underway in California and Texas for separation and processing. Mountain Pass material companies announced in 2025 trial production of NdFeB magnets and a high‑value mixed heavy‑rare‑earth product “SEG+” (containing Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy), which they claim signifies the U.S. regained mid‑to‑heavy separation capability after 30 years — though they avoid specifying purity.

Companies like USA Rare Earth in Texas promote a “mine‑to‑magnet” agenda; in 2025 it acquired UK alloy maker Less Common Metals, long seen as, aside from China, one of the few large producers of rare‑earth metals and alloys. These moves suggest the U.S. is attempting to fill processing gaps.

The U.S. has also poured money into talent recruitment: operator wages are high — on average four times Chinese mining wages — and jobs in this sector increased dramatically between 2010 and 2023. Some Chinese teams were reportedly involved in Mountain Pass post‑investment management, technical support, and trade assistance.

Abroad, the U.S. has sought allies to rebuild supply chains: Australian firms like Lynas and Arafura became partners. Lynas has been hailed as the West’s hope, announcing production of dysprosium and terbium oxides in Malaysia from Australian feedstock — the first time a non‑Chinese company claimed commercial heavy‑rare‑earth output. Lynas is working with the U.S. Defense Department and negotiating with Japanese and Korean firms.

The U.S. and allies also seek technical cooperation: the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act aims to reduce single‑supplier dependence and funds numerous strategic projects across member states and beyond, while Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Estonia, the UK and Japan have reported progress in recycling and substitution technologies. In the West’s media, rare‑earth replacement has at least achieved a “zero breakthrough.”

“Fifteen years to reach zero” — and the emergency fixes behind it

But that “zero breakthrough” reveals the dilemma. In 2010 the U.S. had a two‑year replacement plan aiming to cut Mountain Pass production cost to half of China’s and capture one‑sixth of the market by end‑2012. By 2024, even according to USGS figures, the U.S. share of global rare‑earth production was only about 11.5% — after 15 years of effort, that’s only two‑thirds of a two‑year goal. Even with allied help, they’ve only achieved a modest “zero breakthrough,” which shows how difficult this industrial tree is to grow.

Take Lynas: although it achieved technical milestones, its output and purity are extremely low and cannot displace China in the short term. Environmental concerns have created friction — Malaysia halted Lynas’ separation and leaching operations in 2023 citing radioactive materials.

To replace a mature industrial chain, you must rebuild materials design, roasting/leaching, separation/extraction, magnet manufacture, precise sintering — every link must be rebuilt, an entire ecosystem. A few hundred million from the Defense Department is a drop in the bucket.

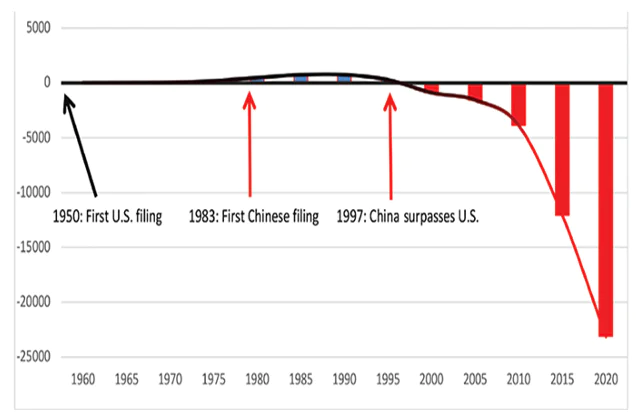

This reflects the West’s deindustrialization and a cliff‑like decline in related patents. Not long ago China suffered technological suppression and sold raw materials cheaply while buying high‑priced products; today the situation is reversed. Over the past 20 years the U.S. has filed fewer than 200 related patents and conducted only small pilot mining operations — there’s little institutional scale.

As U.S. policy intensified, the patent gap widened. Image source: ThREE consulting.

On talent, the U.S. is far from turning the tide. Its approach is to buy foreign talent, while domestic cultivation lags. According to the Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration (SME), U.S. mining graduates per year are fewer than 300; only a tiny share could join rare‑earth work. In the MAGA climate, attracting foreign talent will face political challenges.

By contrast China enrolls thousands of relevant students annually. The West’s separation and refining experts number only in the dozens, while China has thousands. As China builds its expert base and strengthens confidentiality and export controls, the once common practice of Chinese firms helping Western projects post‑investment will likely decline sharply.

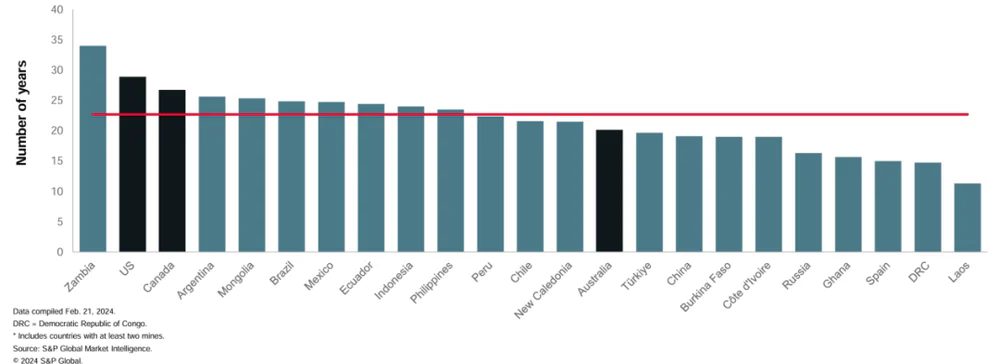

A deeper problem is systemic dysfunction choking administrative efficiency. Since 2010 the U.S. has issued many policies, but implementation has mostly focused on extraction and light rare‑earth processing; extraction is the first major bottleneck. S&P data show U.S. mining exploration budgets are only two‑thirds to one‑half of neighboring Canada’s. From discovery to operation the average U.S. mine development cycle is 29 years — second slowest globally after Zambia.

Comparing average mining development cycles, the U.S. ranks only ahead of Zambia. Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence.

This explains why despite rich minerals, U.S. import dependence has often risen and doubled over two decades. To pursue replacement, the U.S. must hire mercenaries abroad.

Even once a mine is operational, litigation risk is high: U.S. mines attract more lawsuits than Canada and Australia combined. From 2002 onward the U.S. has seen only three mines go into production — not even in the rare‑earth sector, and none on federal land — permitting and litigation are labyrinthine in DC.

Systemic issues also slow down refining and smelting projects. The National Mining Association reports permitting averages 7–10 years in the U.S., while in Canada and Australia it’s about 2 years.

No wonder that despite abundant reserves the U.S. keeps increasing imports: without adequate capital, technology, talent, and infrastructure, domestic replacement is stalled. So they keep trying to grab others’ mines, issuing laws and “framework agreements,” while presidential proclamations of “I won again” fuel headlines, create market rallies, and spawn congratulatory think‑pieces: “U.S. economic outlook is stable and limitless.”

Back to rare earths: rebuilding domestic chain runs into another economic constraint — limited market scale and weak commercial incentives for private investment, forcing government intervention.

Rare earths affect trillion‑dollar industries but the raw market is small. Goldman Sachs estimated the global rare‑earth market at just $6 billion in 2024; many submarkets are tiny. For example, a single F‑35 requires about 23 kg of special magnets — a few tons per year at most. When the U.S. in 2022 pushed for domestic substitution, Mountain Pass retorted: the market is too small; we decline. Capitalism’s blunt reality.

This creates a planning dilemma: Trump promises hundreds of billions, but the market can’t absorb that scale and costs won’t be recouped. To rebuild a full chain you need infrastructure and talent pipelines; too little investment won’t work. It’s a one‑track dead end.

Practically, the Defense Department sprinkled funds, invoking the DPA since 2020 with about $439 million in allocations. That’s not huge. China’s rare‑earth industry in 2011 attracted RMB 6.1 billion in foreign investment. Moreover, military‑style investments often lack clear KPIs: $35 million invested in 2022 in heavy‑rare‑earth processing saw Mountain Pass dodge purity questions and still rely on Australia.

More absurdly, the Pentagon began acting like a venture investor. In July, Mountain Pass announced that the Defense Department bought $400 million in preferred shares convertible to common stock, potentially making it the largest shareholder. The Pentagon both acts as referee and player: it set a $110/kg price floor for Nd output — about twice market price — and pledged to pay the difference and guarantee purchases for ten years; but if prices climbed above $110/kg, the Pentagon would take 30% of sales profits.

Anyone familiar with the “Smith Commissioner” routines will laugh: shares, price supports, purchase guarantees, profit sharing — whole governance conflicts of interest with no economic‑function separation. In a few years we’ll see the price gap between U.S. and Chinese NdPr — and whether the Pentagon’s interventions spawn black markets or political cronyism. Time will tell.

Reuters called this equity deal “setting up a U.S. rare‑earth pricing system to challenge China’s dominance.” Well, enjoy your confidence.

I nearly spewed my soda when I read the exuberant headlines: “U.S. rare‑earth pricing system set to challenge China.” (Photo caption from the article.)

No wonder Americans self‑mock: China has 25 years of lead and an ecosystem that’s hard to shake. The U.S. has pilot plants, trade shows, and press releases.

At root: it’s a systemic problem

This 15‑year U.S. rare‑earth saga is not just about rare earths.

The bottlenecks in U.S. mining reflect permitting systems, federal‑state power allocation, fractured strategic priorities; the failure to build processing capacity exposes the “deindustrialization” curse — capacity, technology, capital, talent, infrastructure, and industrial ecosystem have all collapsed. Ironically, laissez‑faire markets have choked domestic manufacturing, forcing the government to step in to prop up an underperforming sector.

Industry returns haven’t recovered, yet “Smith Commissioners” and “financial geniuses” have profited via the revolving door between business and politics. In my past columns I’ve described similar scripts across sectors — defense, aerospace, steel, and tech — all echoing the same pattern.

What is a systemic problem? It’s comprehensive institutional dysfunction.

We can widen the lens: for years the U.S. has tried to promote rare‑earth replacement, issuing stacks of policies, but progress is slow because of bureaucratic sclerosis, legal complexity, and underinvestment. Trump’s crowing about repatriating manufacturing amounts to bullying for votes; and after a few favorable headlines the markets and certain stocks benefit, while the underlying industrial hollowing persists. Military spending balloons past a trillion dollars, yet even small operations can be sluggish. Meanwhile the stock market is propped up by a few firms — 25 years on, echoes of the internet bubble reappear.

For all the money the U.S. spends, what’s left is financial extraction and remote servicing rather than industrial rejuvenation. It recalls the opening of Dream of the Red Chamber: “Outside, the façade may not yet have collapsed, but the inner pockets are already empty.” Like the Jia family, America has impressive stately things outside but little substance inside.

Shortly after taking office, Trump started gilding the Oval Office — a lavish makeover even as a new presidential plane was delayed for years, with a single paint change quoted at $200 million. Bigger renovations continue under his supervision — that’s the sort of “efficiency” America displays.

Talking with some teachers about rare earths, one suggested China shouldn’t waste energy guessing how far the U.S. will go with its replacement strategy. Two years is the boast; we’ll see if U.S. domestic capacity goes “from mine to magnet” by 2027, whether Lynas can materially dent China’s market share, and whether the U.S.-led coalition can construct a viable supply chain.

In 2027, the Artemis moon program deadline will also loom. The U.S. has made too many vows; most are continuously delayed.

So to conclude: we need not be overly alarmed by the annual shrill headlines — this “shocking” style has been going on for 15 years. In 2010 they hyped U.S.‑Canada‑Australia breaking China’s “monopoly”; in 2020 they hyped dilution of China’s share; each cycle promises a fully integrated global supply chain outside China.

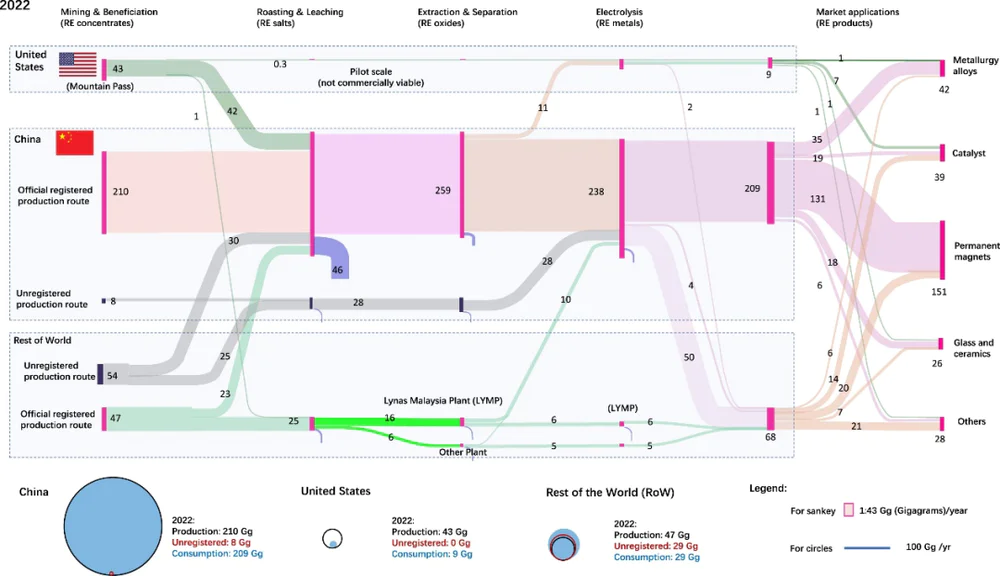

Today, 85% of refined light rare earths and 99% of refined heavy rare earths come from China. Those figures reflect decades of building enormous production lines, supply chains and technology trees, forming a “trinity”: mining (controlling about 70% of global reserves), refining (mature, low‑pollution separation technology), and applications (industry clusters in magnets, optics, energy). Behind these are infrastructure, power grids, process standards, supply‑chain coordination, equipment upgrades, and talent development — an entire ecosystem of mutual reinforcement.

Expecting a single technological breakthrough to replace a whole system is naïve; that “pawns and beasts” thinking is no different from the Taiwanese puppet “we’ve got the Hsiung Feng missile” posturing. Even if disruptive materials appear, the translation from lab to commercial mass production resembles clinical trials — multi‑phase, years in duration. Practitioners know real industry needs accumulation, not noise.

This full supply‑chain illustration shows what a “cliff‑edge lead” looks like. Source: One Earth.

From lab to commercial adoption to mass deployment, 5–10 years is a realistic cycle. The U.S. decision‑makers — many have never run real industry — keep promising “two‑year replacement” plans; that insults industry. With systemic problems, two years is fantasy; even 5–10 years will keep being told as fairy tales.

We can cross‑validate: China has been wielding the “rare‑earth card” since 2010; despite repeated U.S. plays, why do Western partners still perform like newcomers?

That’s why, paradoxically, I am less worried when I see the West making loud threats: “a dog that’s going to bite doesn’t bark much.” For a country that holds large capacity and advanced technology, measured retreat is often required. Instead, integrate into the opponent’s industrial chain and proceed carefully. China historically retreated strategically in many sectors; industry requires cross‑cycle stamina and patience — bluster and puffery won’t win.

This explains why, despite all the racket, China’s market share in rare earths has grown over the years, to the point the West now acts as if only this year did they discover China’s “rare‑earth card.”

Worse still, the Western political class — fund managers, lawyers, NGOs, and media‑born politicians — have no industrial experience and are self‑serving. Billions of taxpayer dollars become opportunities for rent‑seeking. Trump’s bluster aims to placate his base; a few positive headlines feed capital markets and certain firms. The Pentagon “going commercial” is only a symptom of deeper moral hazard. Institutional dysfunction plus personal corruption create a downward spiral.

China’s leadership in rare earths is also a victory of a different system. This system has produced not only rare earths but also gallium, germanium, vitamin C, citric acid, penicillin intermediates, industrial robots, drones, tunnel boring machines, PV modules, EV batteries, LIDAR — from raw materials to finished products, China’s model has driven many industries into positions of indispensability. Rare earths are a reminder: don’t waste this industrial capacity. On this manufacturing foundation we can develop trade, logistics, finance, services, standards and a thousand tactics.

What we lack is continued practice in counter‑sanctions. This year’s series of retaliatory moves should boost confidence and push us to develop more sophisticated counter‑sanction tools.

In the coming years we will continue to see such practice, and witness how our tools make them stumble and fail again and again — until their efforts are finally crushed.

暂无评论内容