At midnight, all was quiet. Cici finally embraced the rare moment of peace in her day. Her two-and-a-half-year-old son slept soundly, though no one knew how long it would last. Despite having access to the world’s top medical resources and a seemingly privileged parenting environment in the U.S., reflecting on the past two years, she told Phoenix Weekly, “Having a baby turns your life upside down.”

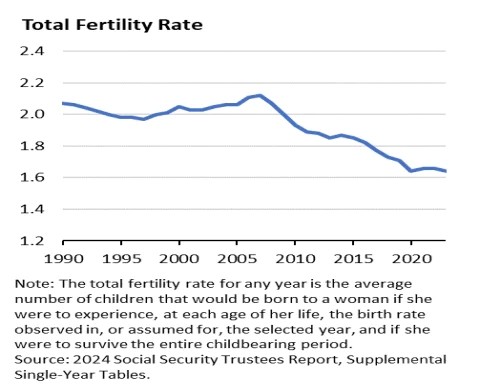

This sentiment is precisely why childbirth has become a persistent headache in America. In 2023, the U.S. total fertility rate hit a 100-year low. While it inched up slightly in 2024, it remains hovering near record lows. The government has scrambled for solutions, with even Democrats and Republicans setting aside their differences to jointly propose a bill mandating private insurance companies to fully cover all childbirth-related costs. Dubbed the “free childbirth” bill, it aims to remove the direct economic barrier to having children.

◆ The U.S. fertility rate continues to decline. Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury

Yet, the American public has not embraced the initiative. On social media, one netizen bluntly stated, “They (lawmakers) are doing the right thing for the wrong reasons. Population collapse will persist until quality of life improves.”

Can “free childbirth” solve the problem?

New York Democratic Senator Kirsten Gillibrand is a co-sponsor of the Supporting Healthy Moms and Babies Act. Introduced to the Senate on May 21 this year, the bill’s core content is straightforward: it compels private insurance companies to fully cover all medical expenses related to childbirth.

According to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), the average cost of pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care in the U.S. reaches $18,865. Even with private insurance, families still pay an average of $2,854 out of pocket. For women with additional pregnancy complications, those on high-deductible health plans, or those facing insurance gaps, the costs are even more staggering—pregnant women are twice as likely to carry medical debt as other women of the same age. The Supporting Healthy Moms and Babies Act was designed to alleviate the direct economic burden of childbirth on American families.

To date, the White House has not officially commented on the new bill. However, one key figure has expressed interest in “free childbirth”: current Vice President J.D. Vance.

As early as January 2023, when he was still a senator, Vance commented on similar pro-natal policies. He voiced support for free childbirth on social media platform X, suggesting that the funds the U.S. sends as aid to Ukraine could “end the surprise bills that destroy new parents’ families and potentially save many new mothers’ lives.”

◆ In 2023, Vance expressed support for free childbirth on X.

If passed, the bill would lead to a moderate increase in private insurance premiums covering 178 million Americans. According to estimates from the Niskanen Center, a U.S. think tank, premiums would rise by an average of about $30 per year. Analyst Lawson Mansell believes that operationally, this may be the simplest way to achieve “no-cost childbirth.”

A mother named “needsanap” on social media platform Buzzfeed shared that an uncomplicated childbirth without insurance costs an average of $30,000 in hospital fees, while a cesarean section can run as high as $50,000. Additionally, without insurance, prenatal doctor visits and care typically cost $100 to $200, and prenatal ultrasounds range from $200 to $300. Even with private insurance, high premiums and deductibles still apply.

For pregnant women, beyond childbirth itself, prenatal medical services are also crucial. The 32-year-old Cici works as an assistant professor at an American university. In 2022, she gave birth at Massachusetts General Hospital, an affiliate of Harvard Medical School in Boston. Despite being one of the top three medical institutions in the U.S., the prenatal care left much to be desired.

“During pregnancy, there were barely any prenatal checkups, and even when they did them, they were quite casual,” Cici recalled. Throughout her pregnancy, she suffered from severe morning sickness, eczema, and muscle pain, but doctors and social workers simply dismissed these as “normal symptoms,” lacking the basic care and effective intervention she had hoped for. Her attending physician repeatedly emphasized, “You have to trust the power of motherhood,” but Cici saw this as a form of veiled moral coercion.

Deng Zi, 35, has two children born in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and both prenatal experiences left a lasting impression. She explained that in the U.S. healthcare system, doctors and hospitals have a cooperative relationship—most prenatal checkups are conducted at the doctor’s clinic, and only childbirth takes place at the hospital. While this model improves convenience, it may also result in insufficiently detailed prenatal care. “The hospital only checked the baby’s eyes, bones, and other parts at birth; there weren’t as many comprehensive postnatal checks,” she said.

◆ According to Deng Zi, babies born in U.S. hospitals undergo basic checks such as temperature, breathing, and hearing. (Photo provided by the interviewee)

In addition to inadequate prenatal care, the length of hospital stays for pregnant women is extremely short, adding to the challenges of postpartum parenting. Due to the private nature of U.S. hospitals, which prioritize bed turnover, women typically stay in the hospital for only 1 to 2 days after a vaginal delivery and 2 to 4 days after a cesarean section. After her cesarean section, Cici cherished the hospital meals and the convenience of nurses helping care for the baby, but her insurance only covered a 3-day stay, forcing her to leave the hospital early with her newborn.

“It was really tough—both of our careers almost came to a halt,” Cici recalled the hardships of caring for the baby alone with her husband after discharge. In Boston, where they live, the cost of a postpartum nanny (yue sao) is as high as $10,000, a prohibitive expense. She described the early parenting period as “basically not sleeping at night.” Deng Zi confirmed this dilemma: “Americans don’t have a culture of postpartum confinement (zuoyuezi), so there are few postpartum care centers in most places. It’s also hard to find a suitable nanny who knows how to take care of babies, and their professionalism varies greatly.”

The Supporting Healthy Moms and Babies Act primarily addresses the out-of-pocket medical costs of childbirth itself, but it fails to tackle the improvement of medical service quality, the refinement of prenatal checks, the improvement of postpartum care support systems, or the underlying commercial logic behind short hospital stays. These invisible, structural barriers are the first major wall deterring parents.

Mounting Challenges on the Parenting Journey

If childbirth is the first hurdle, raising a child after birth involves navigating even more “mountains”: unforgiving parental leave, expensive yet scarce childcare services, and long-term impacts on career development and family finances.

The U.S. is one of the few countries in the world that does not legally mandate paid parental leave at the federal level. While the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) provides up to 12 weeks of unpaid job-protected leave, approximately 40% of women are ineligible. Cici confirmed in the interview that U.S. parental leave is “particularly short,” and even with some benefits, many families cannot access the full 12 weeks.

Marissa Jeanne, a new mother of twins, posted a video on TikTok that resonated with countless Americans. Her twins were born 5 and a half weeks prematurely and spent several weeks in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) before coming home. However, she only had three months of parental leave. “This is my last day with the babies,” she said through tears in the video. After her leave ended, she had to return to work, spending only a few hours with her children each day, leaving her worried and overwhelmed with guilt.

◆ Marissa Jeanne posted an emotional video on TikTok, expressing her reluctance to separate from her twins.

Lin Xiaoxiao, a R&D engineer at an internet company in Seattle, Washington, worked until the day she gave birth to both of her children. Thanks to her company’s generous benefits, she and her husband received 4 months of leave plus an extra month’s salary as milk powder subsidies, making the early parenting period much easier. She admitted that this support allowed them to care for their children independently, but it is not a federal guarantee.

Even after surviving parental leave, childcare is another “mountain.” High childcare costs burden ordinary families. Amber Lord, who has nearly 20 years of work experience and lives in Virginia, was forced to resign after having a child—simple reason: the annual childcare cost of $25,000 exceeded her salary.

Shortage of childcare services is also a major issue. In the college town where Cici lives, childcare resources are extremely tight. “The better childcare centers have waiting lists of over three years,” she said, ultimately having to settle for a part-time childcare program.

After successfully returning to the workplace, these women may also face hidden penalties, discrimination, or even dismissal. Buzzfeed user Maemaeby shared that when she had to take time off to work from home to care for her sick child, some colleagues accused her of being “unserious” and “using childcare as an excuse to get more free time.”

“For me, job security after having children has become the biggest concern,” Lin Xiaoxiao admitted. Amid the current downturn in the internet industry due to AI disruption, she and many friends who returned to work after childbirth feel anxious, fearing potential job adjustments or even layoffs. In the U.S., insurance is usually tied to employment—if a woman loses her job due to childbirth, her medical coverage may also disappear.

Over the past decade, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has received more than 50,000 pregnancy discrimination claims, with nearly one-third involving wrongful termination. A survey of working mothers by the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) and Morning Consult found that approximately 20% of women reported experiencing pregnancy discrimination in the workplace, and 23% had considered resigning due to lack of reasonable accommodations or fear of discrimination.

The academically accomplished Cici once thought she could still “control” her life after becoming a mother, but after more than two years of heavy pressure, she had to reassess the investment required for parenting. Beyond financial and personal capacity considerations, she mentioned many “small but fatal” issues that cannot be ignored—such as whether a partner can provide sufficient support with daily chores like cooking and laundry.

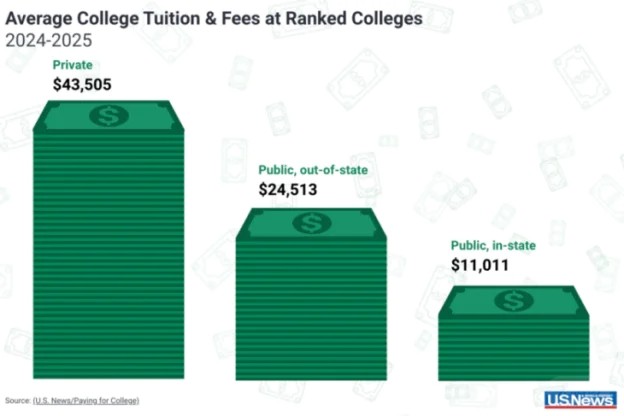

The persistently high cost of education is another sword hanging over every family. Jonas Wen from Oregon has two children, aged two and four. “My wife and I started planning for the future long before our children were born,” he told Phoenix Weekly. “We have a lot to worry about—not just the costs at birth, like diapers and formula, but also future education expenses, especially given the high tuition fees at U.S. colleges and universities.”

◆ U.S. colleges and universities generally charge high tuition fees, especially private institutions. Source: U.S. News

Trump’s New Pro-Natal Policies Fail to Gain Traction

The emergence of the Supporting Healthy Moms and Babies Act is no accident—it is closely linked to the recent intense debate over abortion rights in the U.S.

On June 24, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the nearly 50-year-old precedent Roe v. Wade, which established abortion rights at the federal level. This ruling meant that women’s right to abortion would no longer be protected by the U.S. Constitution. It is widely believed that the three conservative justices nominated during the Trump administration paved the way for the overturn of Roe v. Wade, which is also regarded as Trump’s most significant political legacy. As abortion rights returned to the states, controversies surrounding childbirth intensified further.

Shortly after the Supreme Court’s decision, Elizabeth Bruenig, a contributor to The Atlantic, published an article in July 2022 pointing out that restricting abortion alone—without addressing the economic hardships faced by women of childbearing age, especially the high cost of childbirth—cannot truly reduce the abortion rate. She cited examples of exorbitant childbirth bills and called for free childbirth.

This view sparked deep reflection within the anti-abortion camp. Kristen Day, executive director of Democrats for Life of America (DFLA), a nonprofit organization within the Democratic Party, responded: “This is a very interesting idea.” Catherine Glenn Foster, president and CEO of another nonprofit, Americans United for Life (AUL), also publicly stated: “Free childbirth should be a political issue. I will work to promote this.”

Action followed quickly. In January 2023, the two nonprofit organizations jointly released a policy white paper calling for more comprehensive social support, including treating childbirth as a “free service,” and acknowledged in the acknowledgments that they were inspired by Bruenig. It was this white paper that caught Vance’s attention.

◆ Two pro-life nonprofit organizations jointly released a policy white paper advocating for “free childbirth.”

Ultimately, the bill garnered rare bipartisan support, even winning approval from some women’s rights organizations. Reducing the direct economic burden of childbirth became an important consensus among different factions on the issue of childbirth.

The bill’s introduction received a positive response on Instagram, a social media platform with a large female user base. The comment section was filled with praise: “This is definitely a victory for mothers and new families.” “Great that it’s bipartisan!” Such comments received numerous likes. Jonas Wen also expressed his expectations: “I think this is a step in the right direction. It helps change how parents think and makes society more family-friendly.”

Nevertheless, the prospects and effectiveness of the “free childbirth” bill remain highly questionable.

First, the anti-abortion camp is not monolithic. Some conservative figures are wary of the initiative, believing it could lead the country toward medical “socialism.” Criticism from the left is equally fierce. After Bruenig’s article was published, she faced severe backlash from some progressives, who accused her of “promoting a logic of ‘forced childbirth, just made free,’” forcing Bruenig to deactivate her X account.

More importantly, the bill’s limitations are obvious. As Reddit user Willow-girl put it: “Imagine a woman returning to work after unpaid maternity leave, pumping breast milk in a janitor’s closet, and spending half her salary on childcare. Who would want to do that?” After all, the bill only addresses the cost of childbirth itself, failing to tackle the structural issues behind America’s low fertility rate.

Experiences from other countries also serve as a warning for the U.S. Take Norway, for example. Despite having one of the most comprehensive pro-natal policies in the world—such as generous paid parental leave, universal childcare services, and a quota system encouraging fathers’ participation in parenting—its total fertility rate has dropped from 1.98 to 1.44. Even with strong policy support, fertility rates can decline due to complex social and cultural factors, and the effect of a single economic subsidy is limited .

Against this backdrop, the White House’s recent launch of the “Trump Accounts” program has sparked further controversy. On June 9, during a roundtable meeting with top executives from companies such as Dell, Goldman Sachs, and Uber, Trump officially announced the new plan as part of the “Great and Beautiful Act” recently passed by the House of Representatives.

Under the plan, the U.S. government will establish these accounts for all U.S. citizen children born between January 1, 2025, and January 1, 2029. Specifically, the government will deposit $1,000 into an index fund linked to the entire stock market, managed by the child’s legal guardian. Each child’s account will start with $1,000, and guardians or other private entities can contribute up to an additional $5,000 per year throughout the child’s life. These funds will be invested in index funds tracking the U.S. stock market.

However, the use of funds is strictly restricted: for example, 50% of the balance can be withdrawn at 18, the full amount can be used for entrepreneurship or education at 25, and the entire sum can be freely disposed of only at 30.

In an announcement, the White House claimed: “This will give a generation of children the opportunity to experience the miracle of compound growth and embark on the path to prosperity from the very beginning.”

Yet, financial experts generally question its cost-effectiveness as a long-term savings tool. Despite the positive impact of corporate commitments to additional investments, strict withdrawal restrictions and limited tax benefits make parents more inclined to choose traditional savings methods. Adam Michel of the Cato Institute argues that the plan is “overly restrictive” and unlikely to benefit low-income families.

Regarding the series of “new pro-natal tricks” proposed by the Trump administration, Lin Xiaoxiao commented: “I don’t think they help much because this isn’t the main issue. For professional women like me, the biggest impact of having children is on my career development.”

Cici shared the same sentiment: “As an academic, parenting definitely affects your research publications. Academic positions don’t pay much anyway, so many of my colleagues aren’t interested in having kids.” One of Cici’s female colleagues, who is in the critical stage of pursuing tenure, clearly stated that she chose not to have children to maintain her academic output and quality of life: “After having a baby, I’m afraid I’ll have no savings left.”

Cici admitted that she works in a rapidly developing research field. “Once you take time off for childbirth, some ideas might be developed by others first”—this anxiety weighs heavily on her.

As Benjamin Goss, a scholar at the University of North Carolina, summed up: “People are making quite rational decisions. More often than not, they believe, ‘I want children, but now is not the right time.’”

After more than two years of parenting challenges, Cici has gained a more comprehensive understanding of the so-called fertility dilemma. After half-jokingly advising “don’t recommend jumping into this pit,” she admitted: “Before making this crucial life decision, I hope family members can learn more about all aspects of having children and then make a careful choice.”

|