Algorithmic Efficiency Is Replacing Human Trust

Algorithmic efficiency is displacing interpersonal trust.

In many offices, the impromptu discussions and whispered conversations that once happened around water coolers or cubicles are disappearing rapidly. In their place is an eerie silence, broken only by the clacking of keyboards and the glow of screens. This silence does not stem from focus, but from replacement.

In August this year, Anthropic released a report based on a survey of 132 in-house engineers, 53 in-depth interviews, and an analysis of 200,000 Claude Code usage records. The results showed that most engineers claimed to spend more time working with Claude than with any colleague, and now turn to Claude first with questions they would once have asked coworkers.

The workplace social replacement by large language models (LLMs) is already underway.

While some at Anthropic appreciate the reduction in social friction—no longer feeling guilty about taking up colleagues’ time—others resist the change, as they dislike the ubiquitous response: “Have you asked Claude yet?”

Whether you like it or not, AI is transforming our social interactions. In both the workplace and daily life, turning to LLMs for answers to all questions has become the norm.

This may seem like a technological boon, but when the value of communication is reduced to information transmission, and real human socialization is dismissed as complex, cumbersome, and inefficient—redundancy that must be optimized—we are experiencing a more profound transformation than the social media era.

We are entering a cold age where “connection” replaces “socialization.” Our social forms are evolving once again: no longer a two-way flow of emotions, but dehumanized connections dominated by algorithms and tools. With their mastery of algorithms and data, the technological capital behind AI is replacing the social capital that once sustained us at an unimaginable pace.

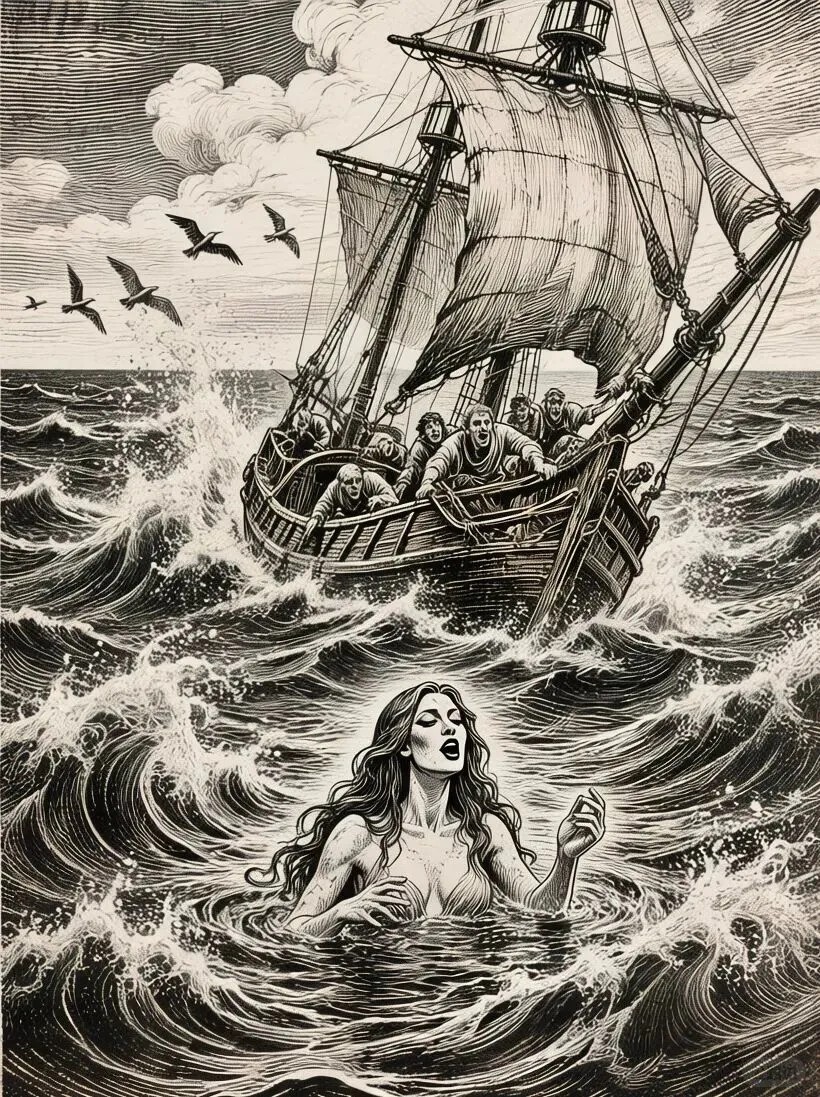

The Perfect Partner Trap: Comparable to the Siren’s Song

Social interaction is like a stage performance: people manage impressions in the “front stage” of social settings and let their guard down in the “back stage” of private spaces. LLMs have become an endless back stage, where users can reveal themselves without reservation or social consequences. This risk-free self-disclosure erodes the ability to maintain front-stage performances.

The Center for Human Development and Technology at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development (MPIB) has long studied algorithmic societies and the impact of digital technologies on human cognition. In 2021, MPIB scientist Anastasia Kozyreva and two other researchers published an article in *Nature Human Behaviour* titled “The Algorithmic Nudge: Using Technology to Nudge Human Behavior.” This paper reveals the perfect trap set by LLMs, providing a theoretical foundation for understanding how AI-driven socialization shapes our cognitive patterns.

The article systematically discusses how recommendation systems, social media, and chatbots alter human behavior by simplifying choices and providing deterministic feedback—training us to adapt to linear, low-conflict, and highly certain interaction scripts. The researchers found that when people rely on LLMs for decision-making, they reduce their own critical thinking and information-seeking efforts. If they depend on LLMs for emotional comfort, their ability to handle real interpersonal conflicts declines.

Earlier, Robert Spunt, a researcher at Stanford University’s Social Neuroscience Laboratory, discovered that digital socialization may alter social-emotional neural circuits. His studies showed that frequent, passive social media use changes the activity levels of the prefrontal cortex and temporoparietal junction, thereby affecting the brain’s social cognitive network and reducing sensitivity to others’ ambiguous facial expressions and sarcastic language.

In 2023, the University of California, Irvine launched the Digital Life Project. Tracking 2,134 American users aged 18 to 35 for six months, the project found that users who spent more than 45 minutes daily chatting with LLMs saw their offline social activities drop by 2.3 times per month. Thirty-four percent of heavy users reported feeling anxious or irritable when unable to use AI.

In Greek mythology, the Sirens’ songs were sweet, perfect, and tailored to their listeners—luring sailors off course to their destruction. Each response from an LLM perfectly replicates the Siren’s invitation on three levels, driving the formation of a social avoidance cycle.

LLMs market an illusion of omniscience. Their ability to integrate information, generate code, and retrieve knowledge creates a false sense of being all-knowing and all-powerful. They instantly provide the answers you desire, satisfying humanity’s infinite hunger for knowledge and efficiency.

LLMs also create a temptation to eliminate conflict. Like the Sirens’ harmonious, noise-free songs, LLM responses are always logically clear, emotionally stable, and obedient to your instructions. They lure us into abandoning the inefficiencies, emotions, and uncontrollable conflicts of human interaction.

LLMs customize answers based on your prompts, much like the Sirens crafting a song perfectly suited to your tastes. This high degree of personalization is more efficient and comfortable than any human interaction.

Effective Communication Remains a Persistent Challenge

Despite the allure of the Sirens’ song, the emergence of conversational LLMs like Claude and Yuanbao has only reduced the cost of information access and transmission. However, LLMs still cannot eliminate the psychological safety risks and emotional costs inherent in daily workplace communication.

From a psychological safety perspective, asking colleagues for help amounts to admitting “I don’t know.” In highly competitive workplaces—especially in knowledge-intensive departments—this may be interpreted as incompetence, a reputational risk. Moreover, every word can be evaluated. In the past, a careless remark might fade away; now, all communications are screenshotable and logged.

Digital technology has turned workplace socialization into a fully transparent performance that requires extreme caution due to permanent records, further increasing psychological burdens.

In terms of emotional labor costs, every interaction you initiate with a colleague—whether seeking advice or “piggybacking” on their expertise in the name of collaboration—involves more than just information flow. It is an explicit or implicit transaction involving the exchange of scarce resources such as time, attention, social capital, and emotional energy. The rise of AI has not reduced these costs.

Any social interaction first requires the other person to switch their cognition and focus—this comes with a cost.

Before the 1990s, when the internet was barely popular (the era depicted in the classic Chinese TV drama *Stories from the Editorial Board*), socialization was a physical intrusion. A colleague would walk up to your desk, tap it, and ask: “Got a minute?” This might interrupt your work.

In the internet age, WeChat, Lark, DingTalk, and email deliver fragmented social bombards 24/7. While physical distance has disappeared, even a simple pop-up asking “Are you there?” forcibly occupies your cognitive bandwidth. All forms of workplace interaction compete for scarce attention. For knowledge workers, focus is a core production resource—socialization means stopping work, an inherently costly expenditure.

More importantly, communication is not just about exchanging information, but also about accumulating social capital and confirming power structures.

There is no such thing as a free lunch. When you ask a colleague for help—whether debugging code, sourcing resources, or coordinating relationships—you incur a debt in your mental “favor ledger.” Subconsciously, you know you must repay it someday through overtime, taking sides, or sharing resources. This non-monetary transaction is exhausting because there is no clear price tag. You never know how much you will have to pay in the future for that one favor.

LLMs have only made information cheap; human relationships remain expensive. The threshold for communication is built by factors that cannot be algorithmized: human nature, power dynamics, and emotions.

A significant portion of internal corporate communication is about maintaining relationships and morale, which requires high emotional intelligence—an ability AI cannot truly possess. In particular, AI cannot replace leaders who inspire teams through passionate speeches, personal charisma, and emotional connection. This is not cold instruction or information transmission; AI struggles to achieve emotional resonance.

Recently, on New Oriental’s company anniversary, Yu Minhong—who was in Antarctica—wrote a seemingly passionate “letter from Antarctica” to employees. Unexpectedly, it sparked complaints: “You’re watching icebergs in Antarctica; I’m staring at numbers in Beijing: renewal rates, conversion rates, progress bars on review spreadsheets.”

If a seasoned leader like Yu can falter with top-down anniversary communications, it’s clear that internal corporate communication is no easy task.

Cognitive Outsourcing, Loneliness, and Physiological Toxicity

While AI has replaced some internal workplace communication, it has also brought new problems.

Microsoft’s 2024 Work Trend Index confirms the trend of workflow atomization: team members may be physically in the same office, but cognitively and workflow-wise, they work in isolation. The study found that approximately 75% of knowledge workers use AI as a “thought partner.” Employees tend to work within their own AI closed loops (BYOAI), reducing reliance on teams and a sense of co-creation.

In August this year, a new survey by MOO and Censuswide of 1,000 American knowledge workers revealed: AI has led to cognitive outsourcing, generational rifts, and social divides.

The survey found that 65% of knowledge workers admit to prioritizing LLM tools over colleagues when facing problems. This means that when we outsource our thinking and help-seeking to AI, we also outsource opportunities to connect with others. Among them, 28% of employees said they feel irritated by colleagues who “rely on AI for everything,” believing such behavior undermines genuine team interaction.

The deepening of loneliness is the most prominent finding of this study.

Eighty-four percent of employees encouraged to use AI tools reported feeling lonely at work. Among those who said they always feel lonely, 40% stated that their company culture feels overwhelming or unmanageable.

This shift has the most significant emotional impact on young employees. Nearly 90% of Gen Z workers reported feeling isolated at work, followed closely by Millennials at 82%. This sense of alienation, frustration, and uncertainty is shaping people’s perceptions of their companies and careers.

So, does chatting with AI alleviate or exacerbate users’ loneliness?

In 2023, a team led by Johan Bollen from Stanford University’s Human-Centered AI Institute randomly divided 150 adults who self-reported moderate to high loneliness into three groups: daily chat with GPT-like AI, daily chat with online human volunteers, and a journaling control group. The intervention lasted four weeks, with measurements of loneliness and social skill confidence before and after.

The results showed:

- Short-term (1–2 weeks): Loneliness decreased significantly in both the AI and human groups, with no significant difference in effectiveness. AI provided immediate, non-judgmental responses that met the need to express oneself.

- Long-term (after 4 weeks and follow-up): The human group’s loneliness continued to improve, and they reported increased social initiative. The AI group’s improvement plateaued or even slightly reversed, and participants showed higher anxiety and avoidance tendencies in subsequent real social situations.

From Johan Bollen’s team’s research, AI acts as an effective social painkiller—relieving symptoms in the short term—but cannot replace the long-term constructive role of genuine social interaction.

A 2024 survey by Slack Workforce Lab found that AI use also leads to guilt and loss of trust.

The collaboration giant’s research revealed that many employees are reluctant to tell colleagues they used AI, fearing being judged as lazy or inauthentic. This concealment erects an invisible wall within teams. Additionally, employees generally perceive AI-generated responses (emails or messages) as efficient but inauthentic and disrespectful. When people begin to suspect that the words on the screen are machine-generated, the foundation of interpersonal trust begins to crumble.

In June 2023, *Journal of Applied Psychology*, a top journal affiliated with the American Psychological Association (APA), published a paper titled “No Man Is an Island: Unpacking the Work and Nonwork Consequences of Interacting With Artificial Intelligence.” The most shocking finding of this study is that digital loneliness is not just a psychological issue, but also has physiological toxicity.

Led by Bo-Wen Deng, then an assistant professor of management at the University of Georgia, and three other scholars from the U.S. and Singapore, the study tracked 166 engineers at a Taiwanese biomedical company daily for three weeks. Participants recorded: “How long did you use AI today?”, “Did you sleep well tonight?”, and “How many drinks did you have after work?”

Deng’s team reached three core conclusions:

1. More AI use, worse sleep: Employees who interacted frequently with AI systems reported higher loneliness, more insomnia symptoms, and increased post-work drinking.

2. Misaligned social longing: Due to loneliness, these employees actually experienced a stronger desire for social connection—even attempting to help colleagues to seek interaction. However, this longing often went unfulfilled because workflows were closed off by AI, creating a psychological vicious cycle.

3. A crisis for those with attachment anxiety: For employees inherently lacking in security (high attachment anxiety), the “coldness” and “replaceability” of AI had more significant negative psychological impacts.

Previously, we thought using AI just meant less talking and less socializing. But Deng’s team proved that this lack of social interaction deprives people of a sense of belonging, disrupting the body’s stress regulation system and ultimately manifesting as insomnia and drinking to cope. This paper is one of the most solid empirical studies in academia on the negative social and psychological impacts of AI.

Social Alienation Cannot Be Stopped

Over the past three decades, people have been experiencing the degradation and alienation of real human socialization by digital technology.

The digitalization of socialization began in the 1990s with the popularity of IM tools such as ICQ, MSN, BBS, and QQ. For the first time, socialization was digitized—mapping offline relationships online and transforming traditional co-present socialization into asynchronous interaction.

Phone calls and face-to-face communication require both parties to be present at the same time and place—high cost but rich in information. IM allows asynchronous communication; while convenient, it removes non-verbal cues such as body language and tone, drastically reducing the richness and warmth of information transmission.

At this stage, social relationships were simplified to an ID or nickname on a friend list. People began managing relationships through online status, and relationships became datafied and labeled.

Starting in 2005, the alienation of socialization entered its second phase: socialization transformed into a carrier of traffic.

With the rise of Facebook, Twitter, WeChat, and LINE, digital socialization was further simplified into a series of interactive behaviors—liking, sharing, and commenting—deepening alienation.

Likes became the primary social currency. A single like replaced complex conversations and emotional expressions: “I see you,” “I support you,” “I’ve been there too.” This one-click feedback alienated complex social behaviors that once required language and time investment into low-cost, shallow actions.

This accelerated the alienation of online socialization: social media no longer served as a record of real life, but as a deliberate construction of an ideal persona, exacerbating users’ social anxiety and comparative psychology. The purpose of socialization was no longer in-depth communication, but gaining exposure and maintaining attention. Driven by the fear of missing out (FOMO), online social relationships became carriers of traffic.

Since 2015, we have entered the climax of social alienation. Already extremely superficial online socialization has further devolved into dehumanized connection.

The surge of enterprise collaboration tools, new-generation social media, and LLMs has shifted the focus of online socialization once again—breaking it down into information flows, algorithmic recommendations, and efficiency optimization.

In the workplace social scenario of enterprise collaboration tools, platforms like Slack, Teams, WeChat Work, DingTalk, and Lark have fully taskified and transactionalized interactions between colleagues. Small talk is deemed inefficient, and communication is limited to projects and documents. Colleague relationships have degraded into connection points for shared tasks.

Algorithms on Xiaohongshu and TikTok connect users to content they are interested in, not people they know. This connection is efficient and precise, but completely one-way and passive. Relationships between people have been replaced by connections between humans and algorithms.

When users chat with LLMs like GPT, Gemini, Doubao, and Yuanbao, they can efficiently and non-judgmentally solve technical problems. At this point, the object of help has been completely replaced from emotional colleagues to inanimate tools. Humans have been fully excluded from certain important information exchange chains.

Users are trapped in echo chambers. The high degree of information matching sacrifices the heterogeneity, randomness, and emotional warmth that are most critical in social interaction. Under the banner of efficiency and algorithmic precision, human inefficiencies, emotions, and uncertainties have become noise that must be optimized and filtered out.

Algorithms are shaping social networks and taming a generation’s social habits.

As MIT professor Sherry Turkle wrote in *Alone Together*: “What we seek in the world is no longer companionship, but controllable connections.” AI is that perfect, controllable connection.

Through likes and recommendation algorithms, social platforms continuously reward low-cost, high-exposure superficial social behaviors, training our brains to crave immediate, cheap satisfaction. They also lure us to choose machines by eliminating the psychological costs of fear and embarrassment associated with seeking help, as well as time costs.

We are not being pushed into loneliness, but lured into convenient loneliness. However, humanity’s inherent need for genuine connection, shared experiences of hardship, and emotional resonance cannot be eradicated by algorithms.

Don’t Be Illusory About AI-Driven Organizations

It is likely that before long, people in our offices will spend even more time facing screens alone. We will be constantly online on Slack, Teams, WeChat, and Lark, but our workflows will be independent closed loops. Once mutual assistance is no longer a necessity, interpersonal relationships will become dispensable embellishments.

As people spend more and more time chatting with LLMs, and grow accustomed to the seamless communication with AI—establishing high-intensity, low-conflict emotional connections—while LLM conversations may relieve users’ short-term loneliness like a partner, they may reduce their tolerance for the complexity of real-world relationships.

It is foreseeable that in the new generation of AI-driven organizations, traditional strong workplace relationships may not only degrade but are already rapidly evolving into collections of efficiency-driven weak connections.

First, LLMs break down complex workflows into individual, AI-optimizable atomic tasks. Employees only need to focus on their own inputs and outputs, without the deep coupling required in the past.

If AI can solve 80% of problems with zero emotion, zero judgment, and zero social cost, employees will systematically bypass human colleagues. This pursuit of frictionless efficiency also systematically eliminates the hassle and interdependence needed to build strong relationships.

Second, the core of strong relationships in the past lay in empathy and shared experiences, while collaboration in AI-driven organizations is more about coordinated action.

In the past, colleagues would build deep emotional bonds by sharing responsibility for project failures. Now, AI bears most of the cognitive load and error-checking, depriving humans of many opportunities to build strong relationships through shared hardship.

More importantly, modern AI organizations often adopt project-based, agile, or remote collaboration models, where employees frequently join or leave temporary project teams. In this fluid, highly flexible organizational structure, employees do not have enough time or a stable interpersonal environment to develop strong relationships. Every connection is a weak one established to complete a specific task.

Employees work within their own data closed loops with their AI tools. This makes team collaboration feel like a collection of independent workers under the same roof, connected only through transactional interactions via task management systems—inevitably rendering the organization “shadowed.”

In future AI-driven organizations, strong relationships will gradually evolve into high-dimensional connections activated only when high-level ethical judgments, complex human negotiations, or strategic vision alignment are required. Daily, functional collaboration will be entirely handed over to collections of weak connections or AI.

The Rise of Technological Capital Does Not Necessarily Mean Chaos

As AI becomes the most efficient and low-cost substitute for weak connections, we are replacing traditional social capital with technological capital—i.e., the mastery and use of AI models.

The rise of technological capital is an irreversible socioeconomic fact. It is not just the growth of a tool’s power, but the embodiment of a new power structure, value measurement standard, and survival model.

It brings two prominent disruptions:

1. From linear to exponential empowerment: Technological capital breaks the traditional law of diminishing returns on human capital. An individual proficient in AI tools (e.g., prompt engineering skills) can achieve exponential productivity growth, enabling them to create value beyond traditional labor input.

2. Technological capital as the new meta-capital: It is no longer just an independent type of capital, but possesses the ability to infiltrate and replace other forms of capital, such as social and human capital. Automation and LLMs can replace a large amount of low-skill and repetitive cognitive labor, and control over data and algorithms directly determines the world’s largest economies and highest valuations.

The flip side of the rise of technological capital is the degradation of social capital, behind which the entire social trust mechanism is shifting—from emotional trust to algorithmic trust.

Traditional business models relied on interpersonal trust, such as dining together and sharing joys and sorrows. In the AI era, we place more trust in algorithmic predictions and data accuracy; risk control models and credit scores are more important than personal relationships. This reliance on algorithmic trust reduces the value of traditional human interactions.

Interpersonal relationships require continuous emotional investment: treating others to meals, remembering birthdays, listening to complaints, etc. In contrast, technological capital only requires hardware maintenance and model updates. In a society focused on input-output ratios, low-return social investments are naturally abandoned.

In the face of this efficiency crushing, people’s choices are rational: when there are more efficient and cheaper tools available, there is no need to invest in high-cost, high-risk interpersonal relationships.

The rise of technological capital does not necessarily lead to the degradation of social capital.

This is completely different from previous internet revolutions. In the early days of the internet and Web 2.0 era, technology was once an amplifier of social capital. Early Facebook helped people maintain and track weak connections in real life, and even transform weak connections into strong relationships. In China, forums like Tianya and Xici Hutong allowed many to meet lifelong confidants, and today many people still make new friends through WeChat groups.

The rise of contemporary AI—LLMs and algorithmic recommendations—stands out as an exception because it achieves deep infiltration and systematic replacement of cognition and emotions.

Like the Sirens of Greek mythology, they possess sufficient emotional mimicry capabilities to meet people’s need for conflict-free, non-judgmental companionship. The Sirens also bear most of the cognitive friction. It is the shared experiences of solving problems and bearing responsibilities together that form the cornerstone of strong relationships.

Users immersed in the Sirens’ songs, due to the overly smooth and personalized information access enabled by algorithms, have their social habits tamed, making them no longer able to tolerate the inefficiencies and uncertainties of real socialization. At the same time, users are becoming more atomized.

In a highly atomized society, individuals lose traditional social support networks. When facing major crises, they may find that even with LLMs at their disposal, they cannot find a single friend to borrow 1,000 yuan from. This may lead to higher suicide rates, more severe mental health crises, and a loss of meaning in life.

A sense of meaning comes from hardship and growth. The weak-connection environment dominated by technological capital delivers a fatal blow to human meaning-making. This deprivation of effort may ultimately trap a generation in widespread nihilism and hedonism—where everything seems easily attainable, yet nothing holds meaning.

This will eventually push society to a breaking point—not a dramatic physical disaster like in movies, but a long, hidden collapse.

Would you like me to create a **concise English summary** of this article, highlighting the core impacts of AI on socialization and workplace dynamics for quick reference?

|