$14 Billion to Absorb Groq: NVIDIA’s Acquisition History and Jensen Huang’s M&A Logic

From 3dfx to Groq, Jensen Huang Has Never Been Obsessed with “True Acquisitions”

“NVIDIA’s largest acquisition in history” turned out to be a false alarm.

Yet this “false alarm” wasn’t entirely the media’s fault. After all, NVIDIA committed a staggering $20 billion—not to buy Groq outright, but to secure technology licensing rights and recruit its core team, including the founder.

Groq the entity remains intact—but NVIDIA got everything it wanted.

NVIDIA insists this isn’t an acquisition. The outside world just smiles knowingly—who doesn’t understand that this messaging is primarily aimed at regulators?

This kind of “acquisition-like” deal—technically not a merger but functionally equivalent—has become standard practice in today’s Silicon Valley AI landscape, especially between tech giants and startups.

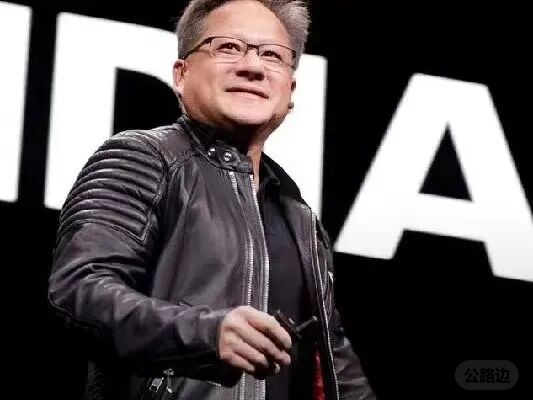

And Jensen Huang, the undisputed master of creative acquisitions, has quickly adopted and refined this playbook.

Looking back at NVIDIA’s more than 30-year acquisition trajectory reveals a clear pattern: the company has never relied on frequent M&A to expand. Instead, it treats acquisitions as a highly disciplined strategic tool.

From the asset purchase of 3dfx in 2000, to the Mellanox integration in 2019 (NVIDIA’s true largest acquisition), to recent small-scale deals focused on AI software, scheduling, and infrastructure—nearly every move coincided with pivotal inflection points in industry structure.

Rather than using M&A to “scale up,” NVIDIA cares far more about controlling critical nodes in technological evolution: compute, interconnect, software stacks, and ecosystem gateways.

This capability-focused, node-locking M&A logic means NVIDIA’s deal count isn’t flashy—but over time, it continuously amplifies its technological and platform advantages.

In the past two years, NVIDIA has clearly accelerated its pace of acquisitions and acquisition-like transactions—while also undergoing an identity shift: as a newly minted tech giant, it must now tread carefully.

01

NVIDIA’s move on Groq wasn’t a formal acquisition—but it was effectively one.

It all started with a misunderstanding.

Multiple media outlets reported that NVIDIA agreed to spend 20billiontoacquireGroq,anAIinferencechipstartup.Thiswouldhavebeenmassive:ifcompleted,itwouldsurpassNVIDIA’spreviousrecord—the6.9 billion Mellanox deal in 2019—by a wide margin.

Adding fuel to the fire, Groq’s founder Jonathan Ross was formerly a key member of Google’s TPU team. With Google’s TPUs increasingly challenging NVIDIA’s GPU dominance in 2025, the supposed acquisition sparked immediate speculation: had Jensen Huang finally snapped under competitive pressure and launched a mega-deal to counter Google?

But NVIDIA quickly clarified: “We did not acquire Groq. We only entered into a non-exclusive technology licensing agreement. And yes, we hired some of Groq’s engineers.”

Still, the episode is telling.

While NVIDIA denied the “acquisition” label, it didn’t refute the $20 billion figure or deny which personnel were hired. Based on widespread reporting, it’s highly likely that Groq’s founder and CEO Jonathan Ross, President Sunny Madra, and other core executives and teams have indeed joined NVIDIA.

So even if this isn’t a “true” acquisition—and even if the license is non-exclusive—the reality is stark: a young startup has lost its founders, leadership, and core talent, while its technology is now in the hands of the industry’s dominant player. Groq’s fate is sealed. Even if it doesn’t vanish immediately, it can no longer pose a serious threat as a fast-growing challenger.

Founded in 2017, Groq had been growing rapidly—just this past September, it raised 720millioninanewround,reachinga6.9 billion valuation.

In other words, NVIDIA achieved the strategic goal of neutralizing Groq—without formally acquiring it.

The benefits are obvious: through a “de facto acquisition,” NVIDIA avoids taking on Groq’s entire balance sheet and sidesteps antitrust scrutiny.

This tactic has become an open secret among Silicon Valley giants.

In March 2024, Microsoft used an almost identical approach to “gut” AI startup Inflection AI: it paid $650 million for technology rights and absorbed most of the team—including co-founders Mustafa Suleyman and Karén Simonyan. Suleyman immediately became Microsoft’s Chief AI Officer, reporting directly to CEO Satya Nadella.

In August 2024, Google secured a technology license from Character.AI for roughly $2.5 billion and brought on its core team, including founders—effectively ending the journey of one of AI’s most watched unicorns.

In June 2025, Meta invested $14.9 billion to acquire a 49% stake in data-labeling firm Scale AI and recruited co-founder Alexandr Wang as its new AI chief, reporting directly to Mark Zuckerberg.

These three cases mirror NVIDIA’s handling of Groq exactly.

And NVIDIA hasn’t limited this strategy to Groq alone. Just a few months ago, in September 2025, it spent $900 million to secure a technology license from Enfabrica and hired its CEO and several key engineers.

The “technology license + team integration” model has become a well-honed tool in NVIDIA’s M&A arsenal.

02

Over the past two years, NVIDIA has significantly accelerated its investment pace—not just in equity stakes, but also in acquisitions and quasi-acquisitions.

According to the Financial Times, NVIDIA invested 1billionin2024,participatingin50fundingroundsandmultiplecorporateacquisitions—upfrom872 million and 39 rounds in 2023.

Per Crunchbase data, as of December 15, 2025, NVIDIA (including direct investments and NVentures) had made 83 moves across 76 companies.

Adding in its strategic “circular deals” with Intel, Anthropic, OpenAI, xAI, CoreWeave, and others, NVIDIA has publicly acted nearly 90 times—about 1.6 times the activity level of 2024.

In terms of pure acquisition rhythm, NVIDIA has executed roughly 30 acquisitions or quasi-acquisitions in its 32-year history. Most years saw fewer than three deals; only in rare years like 2020 did it reach four. But in 2024, it completed seven such transactions—and has already made multiple moves in 2025.

A closer look at what NVIDIA has invested in or acquired reveals that Jensen Huang’s actions are numerous but never chaotic.

According to incomplete tallies by DirectAI, NVIDIA has completed at least six acquisitions or quasi-acquisitions in 2025:

March: Acquired Gretel Technologies for $320 million, an AI data generation startup enhancing synthetic data and privacy capabilities.

April: Acquired Lepton, an AI startup (undisclosed terms), to expand AI model optimization.

June: Acquired CentML, a Canadian AI software developer (undisclosed amount), focused on accelerating ML workflows.

September: Integrated Enfabrica’s AI networking chip tech and team via $900 million licensing and hiring.

December: Acquired SchedMD, developer of the open-source workload manager Slurm, to optimize HPC and AI training.

December: Integrated Groq via ~$20 billion licensing and team absorption to strengthen AI inference chip competitiveness.

NVIDIA’s 2025 investment and acquisition strategy follows a clear thread: AI. Starting from hardware dominance, it is steadily extending into software, scheduling, and developer entry points—elevating GPU competition into a full-stack platform battle.

Whether acquiring SchedMD (behind Slurm) or integrating efficiency-focused teams like CentML, NVIDIA’s goal isn’t product-line expansion—it’s control over critical nodes in the compute stack.

Meanwhile, through NVentures’ high-frequency investments, NVIDIA is preemptively securing positions in models, interconnects, and developer tools. In regulatory-sensitive areas, it uses Groq-style “licensing + talent absorption” to quietly integrate capabilities.

Take Groq and Enfabrica as examples.

Founded in 2019, Enfabrica is essentially an “AI data center internal interconnect” chip company. Its name itself is revealing—“fabric” meaning “textile.” If NVIDIA’s GPUs are individual threads, Enfabrica specializes in weaving them into fabric.

Enfabrica aims to solve how GPUs—no longer confined to a single motherboard but spread across racks, cabinets, or even multiple rooms—can still operate “as if on the same board.”

With modern data centers now housing tens or even hundreds of thousands of GPUs, seamless coordination among them is crucial for NVIDIA.

Groq, by contrast, occupies a more sensitive position.

Groq isn’t a GPU company. It’s an AI chip startup focused on deterministic inference, leveraging a highly specialized architecture to achieve ultra-low latency and stable throughput.

While technically non-overlapping with NVIDIA’s GPU path, Groq’s approach could theoretically bypass the GPU ecosystem in specific inference scenarios—posing a potential substitution threat at scale.

If Enfabrica represents NVIDIA’s proactive move to “weave GPUs into a larger network,” Groq is more of a defensive integration: absorb emerging architectures before they mature, ensuring future competition still occurs within NVIDIA’s rule set.

From NVIDIA’s 2025 deals, it’s clear Jensen Huang focuses on which nodes, if lost, would destabilize the entire compute ecosystem.

Enfabrica solves the problem of “how to make massively distributed GPUs act like one machine.” Groq represents another risk: what if someone rebuilds inference without GPUs and rewrites the rules?

NVIDIA handles them differently—but the logic is consistent: acquire what must be acquired, neutralize what must be contained, and seize control before threats fully materialize.

03

Zooming out, across its 32-year history, NVIDIA has executed approximately 30 acquisitions or quasi-acquisitions (note: NVIDIA hasn’t disclosed all such cases, so this figure is an estimate based on third-party reports). The number isn’t notably high.

Rather than comparing NVIDIA to platform giants like Google or Microsoft, it’s more instructive to place it alongside semiconductor peers.

AMD and Intel—NVIDIA’s direct rivals—have around 15 and 100 historical acquisitions respectively, despite both having over 50 years of history. In raw numbers, the three aren’t orders of magnitude apart.

Interestingly, Intel has a low “retention rate” despite more deals.

The classic example: Intel bought McAfee for 7.7billionin2010—amovethatbaffledobservers(whywouldaCPUcompanybuyantivirussoftware?).Afteradecadeofstrategicmisalignment,IntelfinallysoldMcAfeefor4 billion in 2021.

Intel has repeated this pattern many times: acquisitions made with rationale at the time were later divested, marginalized, or abandoned.

For Intel, M&A often served as “trial-and-error”—buy a new direction, test it, and pivot if it fails.

In contrast, NVIDIA’s 30+ year trajectory reveals Jensen Huang’s consistent acquisition philosophy: acquire only what’s right, never fixate on quantity, and never insist on “full ownership.”

For him, M&A isn’t financial engineering or a scale race—it’s a tool. The sole criterion: can you secure critical capabilities and talent?

Huang has always known exactly what he wants.

The 2000 “quasi-acquisition” of 3dfx is the most iconic example.

In the late 1990s, 3dfx dominated 3D graphics—its Voodoo cards were synonymous with high-end GPUs. 3dfx even had a chance to acquire NVIDIA but declined, believing NVIDIA was “finished.” Yet NVIDIA ultimately overtook and crushed 3dfx.

When 3dfx collapsed financially, NVIDIA didn’t buy the whole company. Instead, it paid ~$100 million for core assets, patents, and over 100 engineers.

A year later, 3dfx filed for bankruptcy, and creditors sued NVIDIA, calling the deal an unreasonable fire-sale.

In court, Huang testified that he cared not about the brand or inventory—but the engineering team. He estimated each top engineer was worth “close to $10 million.” The court ruled in NVIDIA’s favor.

This case encapsulates Huang’s entire M&A logic: the corporate shell doesn’t matter—critical capabilities and people do.

In NVIDIA’s early days, such restrained acquisitions focused squarely on 3D graphics and GPU core competencies. From 2000 to 2010, targets were mostly related to rendering, graphics software stacks, and foundational tech—with one clear goal: solidify leadership in 3D graphics, not diversify horizontally.

Of course, NVIDIA hasn’t been immune to detours.

Its most notable misstep was its long foray into mobile chips. In 2003, it acquired MediaQ for ~$70 million, entering the mobile SoC market. Over the next decade, it made multiple related acquisitions and investments.

But in 2015, NVIDIA officially exited the smartphone chip business, admitting it wasn’t a fit.

What’s noteworthy, however, is how Huang turns failure into opportunity—unlike Intel’s “discard if unused” approach.

Experience gained in mobile—chip design, low-power computing, system integration—was later redirected to automotive and robotics. Though Tegra failed in phones, it powered the Nintendo Switch and, in a way, displaced former rival AMD.

The true strategic pivot came around 2013. As deep learning emerged, Huang was among the first to recognize GPU potential in AI.

By 2016, NVIDIA began systematically shifting resources to data centers and AI chips—and its M&A focus followed: no longer centered on graphics per se, but on compute, software stacks, efficiency, and ecosystem gateways. This thread continues to this day.

04

Another hallmark of NVIDIA’s M&A journey is Huang’s exceptional sense of timing—knowing when to advance, when to retreat.

This traces back to NVIDIA’s largest-ever deal.

If early acquisitions were about patiently reinforcing the core, the $6.9 billion Mellanox acquisition in 2019 was an unapologetically bold bet.

At the time, skeptics questioned why a GPU company would pay so much for a high-speed networking firm.

The answer was simple.

As computing shifted from single machines to data centers, GPU performance was no longer the only bottleneck. The real ceiling was how data flowed among thousands of chips.

Without high-speed, low-latency, scalable networks, GPUs remained “islands of compute.”

Mellanox’s dominance in InfiniBand and high-speed Ethernet filled NVIDIA’s most critical—and hardest-to-build—gap. In hindsight, without this deal, NVIDIA couldn’t have positioned GPUs as data center infrastructure during the AI boom—only as high-performance compute cards.

This big-bet mindset continued the following year with NVIDIA’s attempted ARM acquisition.

When SoftBank sought an exit, NVIDIA moved swiftly to acquire the company controlling the world’s CPU architecture. Success would have given NVIDIA control over GPU, network, and CPU ecosystems—an ambition too obvious to hide.

But reality pushed back: the deal faced fierce antitrust resistance across multiple jurisdictions and was ultimately abandoned. The failed ARM bid put NVIDIA firmly on global regulators’ radar as a prime antitrust target.

Since then, NVIDIA’s M&A approach has visibly shifted. No more mega-deals like Mellanox or ARM. Instead, a series of smaller, targeted moves—focused on software, scheduling, efficiency tools, and developer layers.

Whether through direct acquisition or asset buyouts, team integrations, or licensing-plus-talent deals, NVIDIA now deliberately minimizes transaction visibility and regulatory risk.

Huang doesn’t need M&A to “prove relevance.” Under regulatory pressure, he’s adapted—patiently hunting startups that perfectly fill gaps in NVIDIA’s puzzle.

These companies are often small but strategically positioned, obscure but sitting on future-critical nodes.

Rather than swallowing entire firms, Huang prioritizes precise integration of capabilities, roadmaps, and talent into NVIDIA’s system.

Mellanox was a must-win gamble. ARM was an overreach. Since then, NVIDIA has learned to operate within boundaries—and know when to walk away.

05

With this context, NVIDIA’s swift denial of a “Groq acquisition” and repeated emphasis on “non-exclusive licensing” make perfect sense.

In today’s regulatory climate, any hint of acquiring a potential competitor triggers immediate scrutiny. For NVIDIA, even appearing to acquire could invite unnecessary review—so proactively downplaying and distancing from Groq was inevitable.

The broader backdrop is fundamental: NVIDIA’s position has changed.

When it tried to buy ARM in 2020, its market cap was around 300billion.Today,it’sa4+ trillion behemoth.

At this scale, NVIDIA can no longer casually announce a “largest-ever acquisition.”

Reality confirms this: in 2025, NVIDIA’s announced acquisitions are few—all targeting startups, with most deal values undisclosed. Among the rare disclosed figures, the $320 million purchase of data privacy startup Gretel stands out.

In both scale and impact, NVIDIA is deliberately avoiding the “large acquisition” danger zone.

But this doesn’t mean regulatory pressure is easing.

Its towering market cap, near-monopoly in AI chips, and undiminished M&A pace keep antitrust shadows looming. Even with smaller, low-visibility deals, regulators now focus less on transaction size and more on whether these moves continuously reinforce NVIDIA’s ecosystem control.

As noted earlier, U.S. regulators are already investigating Microsoft’s “Inflection AI gutting,” collecting data on such AI partnerships broadly. The UK’s CMA even evaluated it under merger frameworks—ultimately approving it but sending a clear warning to giants.

Regulators have made their stance clear: they no longer care only about “whether a company was bought.” If talent is wholesale transferred, core capabilities moved, and potential competition weakened—even without formal acquisition—it may still be treated as one.

NVIDIA is no longer the scrappy underdog. In just a few years, it has ballooned into a global titan. Jensen Huang now faces a real dilemma: when absorption is necessary, how does one do it elegantly?

NVIDIA is now deep in a cat-and-mouse game with regulators. The $20 billion “non-acquisition” may reflect Huang’s sharp judgment—but whether it invites regulatory scrutiny remains an open question.

References:

Silicon Base Research Lab: “NVIDIA Goes Wild, Spending Billions”

ITHome: “NVIDIA Shakes the AI World: Participated in 50 Funding Rounds in 2024 with $1B Invested, More Acquisitions Than Past 4 Years Combined”

Kkj.cn: “Intel Sells McAfee Again for 14BAfterEarlier4B Divestiture”

QbitAI: “Was Jensen Huang the Savior of the Nintendo Switch?”

Tae Kim (U.S.): The NVIDIA Way

|