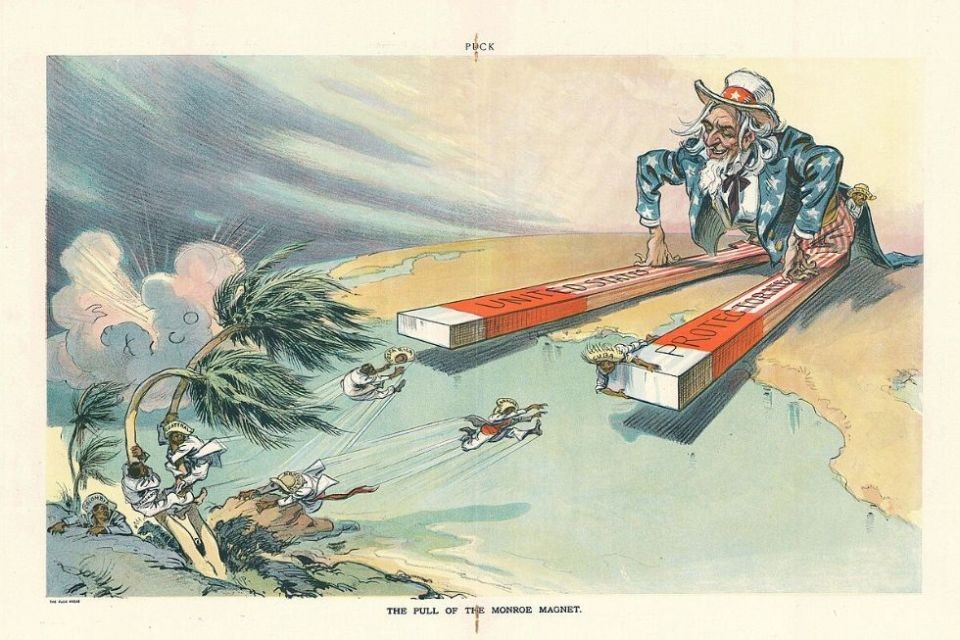

Recently, the Trump administration officially released a new National Strategy document, declaring a full strategic pivot back to the Western Hemisphere and redefining the region as a critical space requiring reinforced dominance. It emphasized consolidating U.S. leadership over regional political, security, and economic order through “enlistment” and “expansion.” Against this backdrop, the Venezuela crisis is not merely an isolated regional conflict but rather a concrete manifestation of this strategy—an operational blueprint that reveals the logic behind Trump’s policies in Latin America.

U.S. policy toward Venezuela has never rested on a single rationale. Instead, it continuously repackages its narrative—from “restoring democracy” to “combating drugs,” and more recently to “counterterrorism”—to lend an air of legitimacy to sustained pressure. Since last September, this approach has been pushed to an extreme. Without presenting public intelligence evidence, the Trump administration labeled President Nicolás Maduro as the leader of a so-called “Cartel of the Suns,” branding him a “global terrorist” engaged in “narcoterrorism.” Citing the need to “prevent drug-related deaths of innocent Americans,” Washington launched large-scale maritime “anti-drug” operations in both the Caribbean and the Pacific, even openly threatening that military intervention could escalate from sea to land.

However, both the operational methods and geographic logic undermine the credibility of this “anti-drug” justification. Traditional U.S. counter-narcotics efforts have been law-enforcement–oriented, led primarily by the Coast Guard, focusing on intercepting drug shipments, arresting suspects, and processing them through judicial channels—not deploying heavily militarized forces to directly threaten a sovereign government. Geographically, the primary source of U.S. drug inflows has long been the Pacific corridor, with vast quantities of narcotics entering the U.S. via Colombia and other countries along Pacific routes. If the true objective were genuinely anti-drug, U.S. military assets should be concentrated in the Pacific—not the Caribbean. These deployments clearly do not align with the practical requirements of conventional drug interdiction.

The real core of U.S. actions against Venezuela remains the pursuit of control over the country’s critical resources through sustained pressure—and potentially regime change. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, primarily composed of extra-heavy crude that requires advanced technology and massive capital investment for extraction. Due to weak infrastructure and years of sanctions, this potential has remained largely untapped. Meanwhile, the U.S. domestic oil industry is maturing and showing signs of stagnation. In this context, undermining Venezuela’s oil exports serves a dual purpose: it severs the Maduro government’s main fiscal lifeline, systematically weakening its governing capacity, while simultaneously creating strategic opportunities for U.S. energy capital and domestic economic interests.

The EIA has even explicitly noted that Venezuela’s heavy oil is “highly suitable” for U.S. refineries, especially those along the Gulf Coast. White House Chief of Staff Susie Wiles, in a Vanity Fair interview, bluntly stated that Trump “wants to keep blowing up ships until Maduro says, ‘I surrender.’” This near-candid remark lays bare the true logic of U.S. policy: the goal isn’t drugs—it’s using escalating external pressure to force political and strategic concessions from the Venezuelan regime.

Historically, this isn’t the first time the U.S. has invoked “anti-drug” rhetoric to advance strategic objectives. In 1989, Washington invaded Panama under the banner of “counter-narcotics,” swiftly overthrowing President Manuel Noriega and accusing him and his government of drug trafficking. Decades later, it’s recycling a similar legitimizing narrative—this time accusing Venezuela’s leadership of involvement in drug cartels. Neither Panama nor Venezuela was randomly selected: one controls the Panama Canal—a global shipping chokepoint; the other possesses the world’s largest proven oil reserves. Both hold irreplaceable strategic value. Yet the international contexts of these two interventions are starkly different.

The Panama operation occurred at the tail end of the Cold War, when the U.S. operated in a highly asymmetric global environment with minimal fear of great-power backlash. Latin American nations then lacked the capacity to effectively counter U.S. military action, enabling a swift, low-cost intervention. Today’s Venezuela crisis, however, unfolds in an era of accelerating multipolarity and intensifying great-power competition—a setting that favors prolonged, hybrid pressure rather than decisive military strikes, with an uncertain escalation path.

Given current constraints, the U.S. is more likely to pursue a strategy of “sustained pressure while awaiting internal fracture”: layering economic sanctions, military deterrence, diplomatic isolation, and political support for the opposition to steadily shrink Maduro’s strategic maneuvering room. When necessary, Washington may also carry out targeted sanctions or precision strikes against high-ranking officials accused of “terrorist activities.” By contrast, the likelihood of a full-scale military invasion remains low. Without clear international legal authorization or domestic political consensus, launching a military intervention against a sovereign state would likely trigger fierce controversy at home and entail unpredictable, high strategic costs. Transoceanic military operations demand long-term troop deployments and massive financial outlays—risks that could easily spiral into an unwinnable quagmire.

Nevertheless, the U.S. has already begun planning for a “post-Maduro Venezuela.” Opposition leader María Corina Machado has submitted a detailed transition blueprint to the Trump administration, outlining key policy measures for the first 100 hours and 100 days of a new government. Meanwhile, political transition frameworks developed during Trump’s first term are being revisited and deemed still applicable under current conditions. Yet even with these contingency plans, it remains highly uncertain whether Washington can successfully install—and sustain—a stable, effective, and genuinely pro-U.S. government. A power vacuum could instead trigger prolonged political chaos and security risks, potentially dragging the U.S. into an even costlier regional entanglement.

On December 23, the UN Security Council convened an emergency session on the Venezuela situation.

For Venezuela itself, the Maduro regime retains, for now, a degree of resilience to absorb the political costs of ongoing currency depreciation, collapsing public services, and repressive governance. But this comes at the price of further hollowing out and fragilizing its social and economic foundations. In the medium to long term, without relief from sanctions or resolution of structural domestic issues, deepening economic decline and mounting social pressures will likely fuel mass emigration and systematically erode state capacity. Under relentless internal and external pressure, cracks within the regime—and potential power realignments—are becoming more probable, though such a process is likely to be gradual rather than abrupt, carrying immense social costs and prolonged instability.

The spillover effects of the Venezuela crisis are already reshaping Latin America. For instance, the Trump administration has cut aid to Colombia and publicly labeled President Gustavo Petro an “illegal drug kingpin” on social media and in official statements. After a drone strike killed Colombian citizens, the U.S. refused to assume responsibility—actions widely interpreted as extensions of its “security and anti-drug” pretext to exert political and economic pressure on regional states. Under the same strategic logic, countries like Cuba and Nicaragua—long at odds with Washington—are also likely to remain prime targets of sanctions, blockades, and covert operations, all aimed at preserving U.S. capital and security dominance in the hemisphere.

Yet it remains doubtful whether this heavy reliance on coercion and deterrence can actually deliver the political outcomes the U.S. desires in Latin America. Ironically, Venezuela—once increasingly marginalized even among traditional regional allies—has seen its geopolitical position partially rehabilitated due to Washington’s escalating military threats and securitized rhetoric. This has heightened wariness among other Latin American nations toward U.S. regional conduct, eroding trust in American intentions and, paradoxically, narrowing the political distance between them and Caracas.

From “anti-drug” to “counterterrorism,” the U.S. keeps updating its interventionist rhetoric—but the underlying logic remains unchanged: cloaking geopolitical and resource-driven ambitions in moralistic language. History repeatedly shows that U.S. military interventions in Latin America often yield catastrophic consequences. Regardless of the Maduro regime’s many flaws, unilateral external military action by the U.S. is certainly not the solution. As “Trump-style Monroeism” resurges, whether Latin American nations can leverage diversified diplomacy and issue-based flexibility to carve out greater strategic autonomy will be the decisive factor shaping the future order of the Western Hemisphere.

|