Is Japan’s senior leadership visiting Russia part of a “horizontal alliance” maneuver by Sanae Koike aimed at China? And will Putin actually accept this “Christmas gift” from Tokyo?

Japanese High-Level Delegation Visits Russia: Koike Stabs China in the Back—Will Putin Give Face as Long as the Gift Is Delivered?

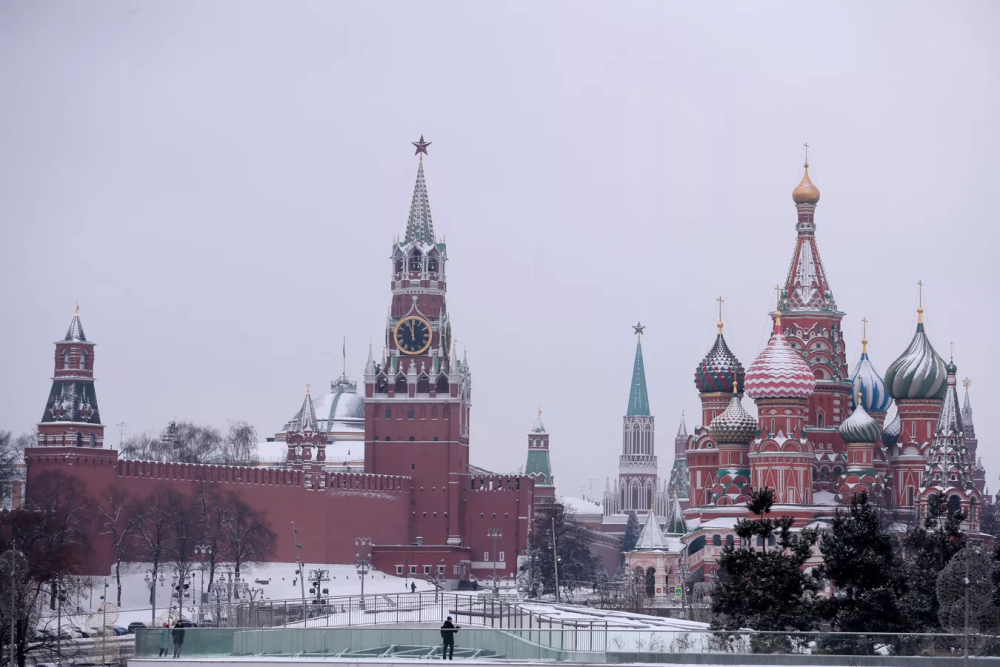

In the early hours of December 25 Beijing time—just as Western nations celebrated Christmas—a flight departed Tokyo under cover of night, heading for Moscow. Sanae Koike was sending Vladimir Putin a “Christmas present.”

The main passenger aboard this special aircraft was Munenori Suzuki, a veteran lawmaker from Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Officially, Suzuki’s trip aimed to discuss the sovereignty issue over the Southern Kuril Islands (Northern Territories), seeking Russian permission for Japanese citizens to fish there and “visit ancestral graves.”

But observers understand clearly that this high-level Japanese visit to Russia is far more than it appears on the surface. At the very moment Suzuki set off, the Koike administration unveiled a record-breaking fiscal year 2026 budget, with defense spending exceeding the 9 trillion yen mark for the first time ever.

Meanwhile, Japanese media reported that Koike is likely to visit the Yasukuni Shrine soon. Taken together, it’s evident that the Koike government’s primary objective is to seek Russia’s tacit acceptance—or at least non-opposition—to Japan’s accelerating militarization.

Suzuki’s Moscow trip was no coincidence. A seasoned politician with 40 years of experience, Suzuki has long styled himself as “pro-Russia,” advocating for a peace treaty and deeper bilateral ties with Moscow.

More importantly, Suzuki maintains close personal ties with senior Russian officials, including Deputy Foreign Minister Alexander Galuzin, who previously served as Russia’s ambassador to Japan and collaborated extensively with Suzuki.

The itinerary itself carried strong symbolic overtones of “gift-giving.” In addition to meetings with Russian foreign ministry officials, Suzuki specifically arranged a visit to the memorial site for Soviet Red Army martyrs.

Given that Russo-Japanese relations have plummeted to freezing point in recent years due to the Ukraine crisis and Tokyo’s sanctions against Moscow, Suzuki’s gesture was widely interpreted as a goodwill signal aimed at “repairing” bilateral ties.

Koike’s choice of Suzuki—rather than a higher-ranking official—was itself a calculated balancing act: signaling openness to engagement while preserving diplomatic flexibility.

Her foremost goal is to “break the deadlock.” Japan currently faces unprecedented diplomatic challenges. On China, Koike has repeatedly tested red lines on Taiwan and military security issues, driving Sino-Japanese relations into deep freeze.

On Russia, Japan has followed the West in imposing multiple rounds of sanctions, provoking strong Russian backlash—including Moscow’s March 2024 announcement halting all peace treaty negotiations with Tokyo.

Digging deeper, the Koike administration is attempting to “drive a wedge” into the increasingly solid China-Russia partnership. The two countries’ aligned positions on regional security pose significant strategic pressure on Japan.

Tokyo hopes to “defeat them one by one.” Even if Suzuki’s mission fails to immediately shift Russia’s stance, it aims to “introduce some uncertainty” between Beijing and Moscow, buying Japan crucial breathing room.

But as expected, Koike’s “gift” was met with an icy rebuff before it could even be delivered. On December 25, Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova issued a series of sharp statements. First, she warned that if Japan abandons its non-nuclear status, it would violate its international obligations and “inevitably trigger countermeasures.”

Then she launched a full-scale attack on the Yasukuni Shrine, declaring it “a loathsome symbol of Japanese militarism.” In her view, Japan should “build a temple honoring the victims of Japanese militarism” to atone for its inhumane wartime atrocities.

|