Many people are reluctant to admit it, but a harsh truth is being increasingly confirmed by mounting historical evidence:

In 1945, Japan wasn’t subdued by two atomic bombs—it was cornered with no way out.

Had those explosions not occurred, Japan wouldn’t have faced a gentler outcome, but a far more total collapse.

This isn’t about whitewashing anyone—it’s a cold, logical dissection of war.

1. Was Japan really on the verge of surrender before the atomic bombs?

Many assume Japan was already on its last legs.

But reality tells a different story.

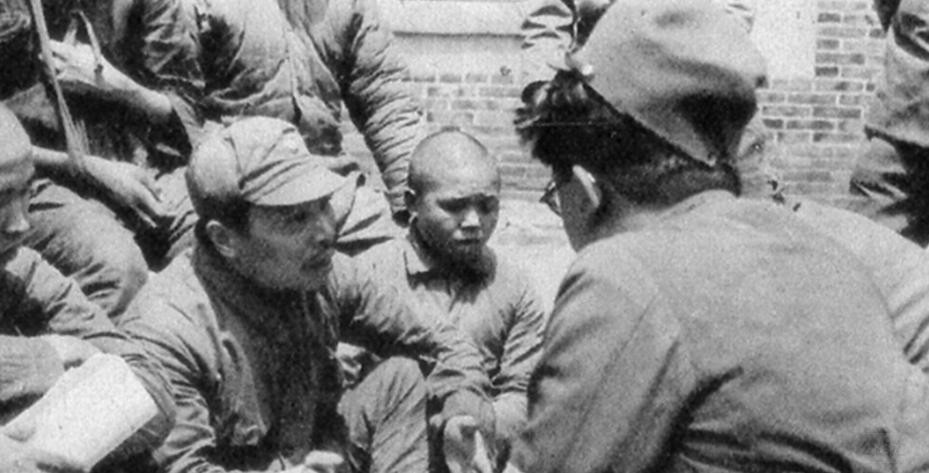

In the summer of 1945, Japan’s political system hadn’t collapsed; the military command remained fully operational, and plans for homeland defense were already in place.

Their core strategy wasn’t victory—it was prolonging the war until American society could no longer bear the cost.

Not to win battles, but to make the enemy bleed more.

Okinawa had already served as a preview for the Allies.

On that relatively small island, casualties shocked the U.S. public and sparked serious internal debate.

And mainland Japan’s population density and societal mobilization capacity far exceeded Okinawa’s.

If the fighting reached the home islands, the consequences were clear.

2. What truly terrified Japan wasn’t just America

Most discussions focus solely on U.S.–Japan dynamics, missing a critical third player:

the North.

At the time, Japan still clung to hope—seeking third-party mediation to secure a relatively intact postwar arrangement.

As long as the imperial institution (kokutai) survived, everything else was negotiable.

But the situation shifted abruptly—not because Tokyo was bombed again, but because the strategic landscape flipped overnight.

The entry of northern forces sent a crystal-clear message to Japanese leaders:

this wasn’t just about bombing—it meant their entire political structure risked being uprooted.

Prolonging the conflict could easily split Japan into two—or more—entities.

History had already provided such precedents.

3. The real role of the atomic bomb in great-power calculus

The atomic bomb wasn’t merely a weapon of war—it was a tool of negotiation.

It abruptly ended the phase of attrition and forced an immediate termination point.

For the user, it compressed timelines and reduced uncertainty.

For the target, it offered a face-saving excuse:

defeat could be blamed on a revolutionary weapon, not systemic failure;

surrender could be framed as unavoidable, not a total repudiation of the past.

That’s why the postwar order solidified so quickly—

many structures that might have been dismantled were selectively preserved.

Not out of kindness, but for efficiency.

4. Why does this still matter today?

Because the same logic hasn’t vanished—it’s just taken new forms.

When a system can’t self-correct, costs get pushed downward.

When escape routes are sealed off, extreme choices start looking like the “only option.”

For ordinary people, the greatest danger has never been conflict itself—

but being locked into a decision chain with no brakes.

Conclusion

Looking back at that era, an unsettling pattern emerges:

Great-power “rationality” is often built upon unbearable suffering inflicted on others.

The atomic bomb didn’t save anyone.

It merely ended a longer, more chaotic destruction ahead of schedule.

The real question is:

Next time the world reaches another “no-way-out” moment—

who will be allowed to end things… gracefully?

|