In recent years, China has seen a rise in independent bookstores founded out of the personal passions of their curators, sparking a phenomenon dubbed the “small bookstore renaissance.” Yet this brief flourishing is now receding, as an aging industry contends with China’s slowing economic growth and increasingly constrained cultural spaces.

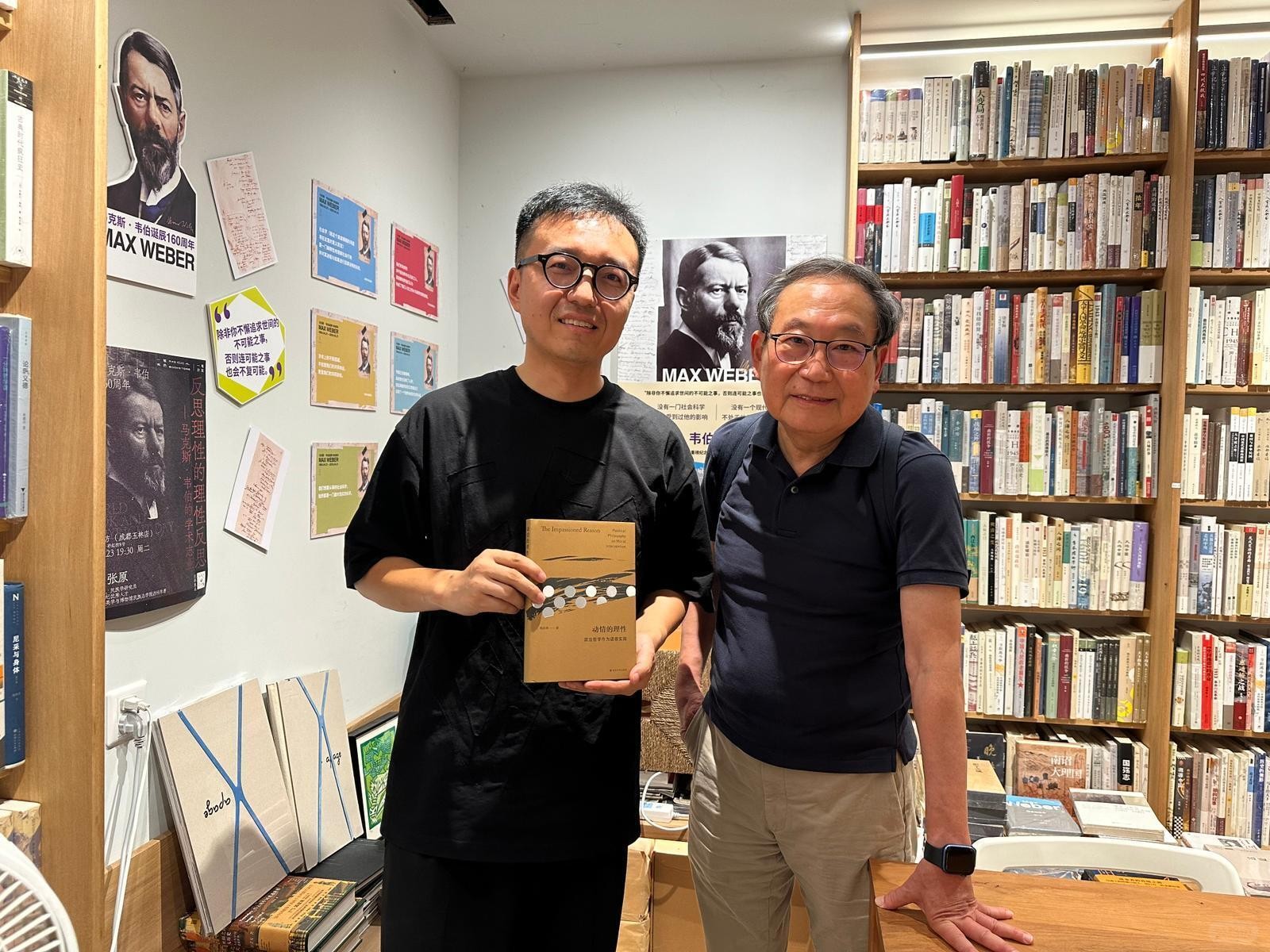

China has recently witnessed a wave of curator-led bookstores—establishments born from founders’ personal interests that go beyond selling books, coffee, and cultural merchandise. Some have placed greater emphasis on creating public living spaces and hosting events that engage with social issues. Pictured is a scene from an event at Yiwěi Bookshop in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. (Photo provided by Wang Jun)

Fang Xuxiao, a Chinese book critic jokingly called a “bookstore fanatic” by friends, defied the prevailing trend of e-commerce and livestream book sales by releasing a new book, Bookstore Calendar 2026, available exclusively in physical bookstores. The book documents independent bookstores across China through illustrations and interviews, capturing their diverse styles and spirits.

Having worked both as a bookstore clerk and a senior publishing executive, Fang has long traveled across China visiting bookstores. He told Lianhe Zaobao he wanted this book to be something “uniquely for bookstores,” as independent stores face unprecedented challenges. “If more products like this are offered to bookstores by the publishing world, I believe they’ll find a new path to survival.”

Official data shows that in China’s RMB 112.9 billion (SGD 20.6 billion) book retail market, physical bookstores now account for only 14% of sales. The state-owned Xinhua Bookstore system—representing just 1.5% of all bookstore outlets—captures over 30% of physical bookstore revenue, leaving private independent bookstores struggling to survive in the narrow gaps.

The difficulty of making money from selling books is a shared global reality for the industry. Nevertheless, the number of independent bookstores in many Chinese cities continued to grow against the odds in recent years, fueling a curator-led bookstore trend.

These passion-driven bookstores not only sold books, coffee, and文创 products but also sought to build communal public spaces, organizing discussions on social issues. During the height of pandemic lockdowns, they provided much-needed venues for face-to-face interaction, becoming spiritual landmarks in urban life. Yet over the past year, many of these very bookstores have shuttered one after another.

Fang believes most independent bookstore curators are quintessential idealists or artsy youth who “open a store on an impulse.” However, rising rents, economic slowdown, and declining consumer spending have all dealt severe blows to their operations.

With Strong Personal Identities, Independent Bookstores Enter “Version 3.0”

Zhu Yan, founder of Chengdu’s Wild Pear Tree Bookstore—which closed in June last year—cited not only the worsening macroeconomic climate but also increasing regulatory restrictions on bookstore events. “The atmosphere in the industry has changed dramatically,” he said in an interview. “I feel deeply disillusioned.”

In 2022, as China gradually emerged from pandemic lockdowns, several independent bookstores—including Wild Pear Tree—opened in quick succession in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan Province. Zhang Feng, a Chengdu-based commentator, wrote at the time on his WeChat public account that China’s bookstore industry was undergoing a major transformation: “Driven by the distinct personalities of their curators and built around small, tight-knit communities, bookstores have entered version 3.0.”

China’s private independent bookstores have evolved over more than three decades. Beijing’s Wansheng Book Garden and Shanghai’s Ji Feng Bookstore, both opened in the 1990s, represent the first generation. Recalling those days, Fang said, “Back then, there wasn’t even a concept of ‘independent bookstores.’ They sold only books—nothing else.”

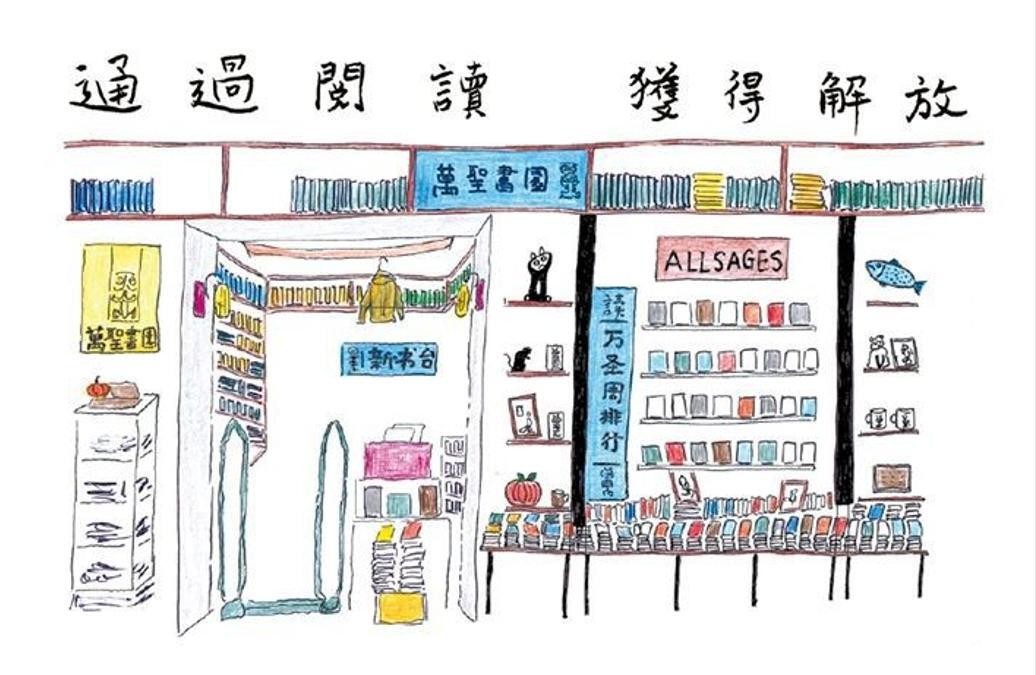

Pictured is an illustration of Wansheng Book Garden drawn by Fang Xuxiao. (Provided by Fang Xuxiao)

Chain bookstores like Danlan Street (One Way Street), founded in the early 2000s by Chinese cultural figures such as Xu Zhiyuan, are regarded by Fang as the second generation. “Independent bookstores started being called ‘independent’ roughly from the era of literary bookstores represented by Danlan Street.”

Later, chain brands like Yanjiyou and Zhongshuge rose with capital backing, often creating “most beautiful bookstore”网红 spots inside shopping malls. However, Yanjiyou—which once operated over 50 stores nationwide—faced a cash crunch during the pandemic and has since nearly vanished entirely.

Around the same time Yanjiyou collapsed, the third generation of independent bookstores began to emerge. Fang noted, “Bookstores are increasingly rooted in personal tastes or interests, and those bearing strong curator or owner identities are becoming more common.”

Second-Tier Cities Briefly Witnessed a “Bookstore Renaissance”

Wang Jun, curator of Chengdu’s Yiwěi Bookshop, told this newspaper that today’s bookstores are no longer just places to sell books—they are “cultural spaces for content creation.” “Chengdu has sci-fi-themed bookstores, literature-focused ones, feminist bookstores, secondhand shops—and most independent bookstores here lean toward humanities and social sciences.”

Zhang Feng contrasted them with commercial chains: “The manager at a Yanjiyou store is an anonymous worker, while independent bookstore curators have strong individuality. They openly express aesthetic preferences and may reject certain books, authors, or even readers from entering their space.”

He cited Wang Jun as an example: “I know several bookstore curators who would feel offended if you asked for self-help or success manuals—they possess a spirit of negation, and that is precisely the soul of an independent bookstore.”

Wang Jun opened Yiwěi Bookshop in October 2019 in Chengdu’s lively Yulin neighborhood. Specializing in humanities and social sciences, the store regularly hosts salons and reading groups covering philosophy, history, art, anthropology, and social issues.

Shortly after opening, the bookstore encountered the pandemic—but unexpectedly, this became an opportunity for events. Wang recalled that from summer 2020 to winter 2022, Yiwěi held about 100 offline events per year, sometimes two or three weekly.

Wang Jun (left) has run Yiwěi Bookshop in Chengdu since October 2019. Pictured is Wang with Taiwanese scholar Chien Yong-hsiang inside the store. (Photo provided by Wang Jun)

Wang reflected that during the pandemic, bookstores weren’t classified as restricted venues like restaurants or bars—“there was a loophole.” He didn’t think visitors were particularly passionate about culture; rather, “people urgently needed a physical space for face-to-face interaction.”

Zhu Yan’s Wild Pear Tree Bookstore opened in June 2022 and hosted over 1,000 events in its three years before announcing its “honorable closure” in June last year.

In his closure notice, Zhu wrote that when the store opened, Chengdu was still under lockdown: “I remember how people in our WeChat group helped strangers—sharing ibuprofen and fever reducers, buying groceries, feeding pets, sheltering those stranded on the streets. In despair, we supported each other.”

Zhu Yan (center) opened Wild Pear Tree Bookshop in June 2022. Pictured is Zhu at one of the store’s events. (Photo provided by Zhu Yan)

Bookstores like Yiwěi and Wild Pear Tree helped make Chengdu’s independent bookstore scene a nationally noted cultural phenomenon post-pandemic, frequently featured in media targeting China’s middle class. Chengdu’s government has repeatedly promoted the city as home to over 3,500 physical bookstores—the highest number in China.

In 2024, Xu Jilin, a history professor at East China Normal University in Shanghai, observed at a public event that Chengdu has long had a teahouse culture emphasizing public life. Now, young people go to bookstores instead. “They chat every night about all kinds of topics… So far, Chengdu hasn’t been tightly controlled—they figure you’re just chatting anyway. In this regard, its openness even exceeds that of Beijing or Shanghai.”

Post-Pandemic Economic Downturn Makes Operations Harder

Fang Xuxiao noted that not just Chengdu, but also Chongqing, Hangzhou, and other second-tier cities have developed vibrant independent bookstore ecosystems—a “small bookstore renaissance”—because “after being locked down for three years, people really wanted to get out and do things.” Small cities are also seeing more independent bookstores, often started by young people returning from big cities who bring mature cultural concepts to their hometowns.

But this Chengdu-centered wave quickly faced post-pandemic challenges. Wang Jun revealed that Yiwěi broke even during the pandemic, but performance deteriorated in 2023. “The overall economy is slumping. Our customers are mostly young, and youth unemployment is terrible—they cut back on non-essential spending.”

In the second half of last year, a friend’s planning company transformed Yiwěi into a hybrid exhibition space and café. “We still hold events, but books now take up less space,” Wang said, acknowledging that “every bookstore struggles differently—we’re all just hanging on, seeing who lasts longest.” He admitted he’s now in debt: “My original model has lost money for two straight years. I simply can’t hold on anymore.”

Zhu Yan also cited macroeconomic conditions and operational costs, but emphasized growing regulatory constraints: “There’s less and less we’re allowed to do,” which heavily influenced his decision to close.

Operators: A Good Era Seems to Be Over

For example, an annual independent bookstore fair in Chengdu was abruptly canceled on the day of the event last May, after Wild Pear Tree had spent days preparing. “All that effort went to waste—it really crushed morale,” Zhu said.

Zhang Feng, who launched Youxing Bookstore in Chengdu in 2023, listed in a September post multiple closures—including Wild Pear Tree, Changye Bookstore, Yi Niao Books, and Guopi Books—and declared, “Chengdu’s literary scene is dying” and “a good chapter for Chengdu’s independent bookstores seems to be over.”

His words proved prophetic. In late October, Zhang suddenly announced Youxing would close due to “force majeure,” triggered by its public-issue lecture series drawing outside attention. Rumors spread that official scrutiny followed media coverage of the closure. Days later, Zhang posted again: “Thank you, everyone”—the store could stay open, as “your love created some miraculous effect.”

Fang Xuxiao believes Chengdu’s brief boom was natural—bookstore founders are inherently idealistic, but keeping a store alive is hard. Many small independent bookstores in China cycle through openings and closures; it’s “a very natural ecosystem.”

“No matter how many people warn others not to open bookstores—even owners themselves saying so—there will always be someone rushing in,” he said.

Illustration / Lu Fangkai

Cities Grow Homogeneous—Bookstores Reveal Local Uniqueness

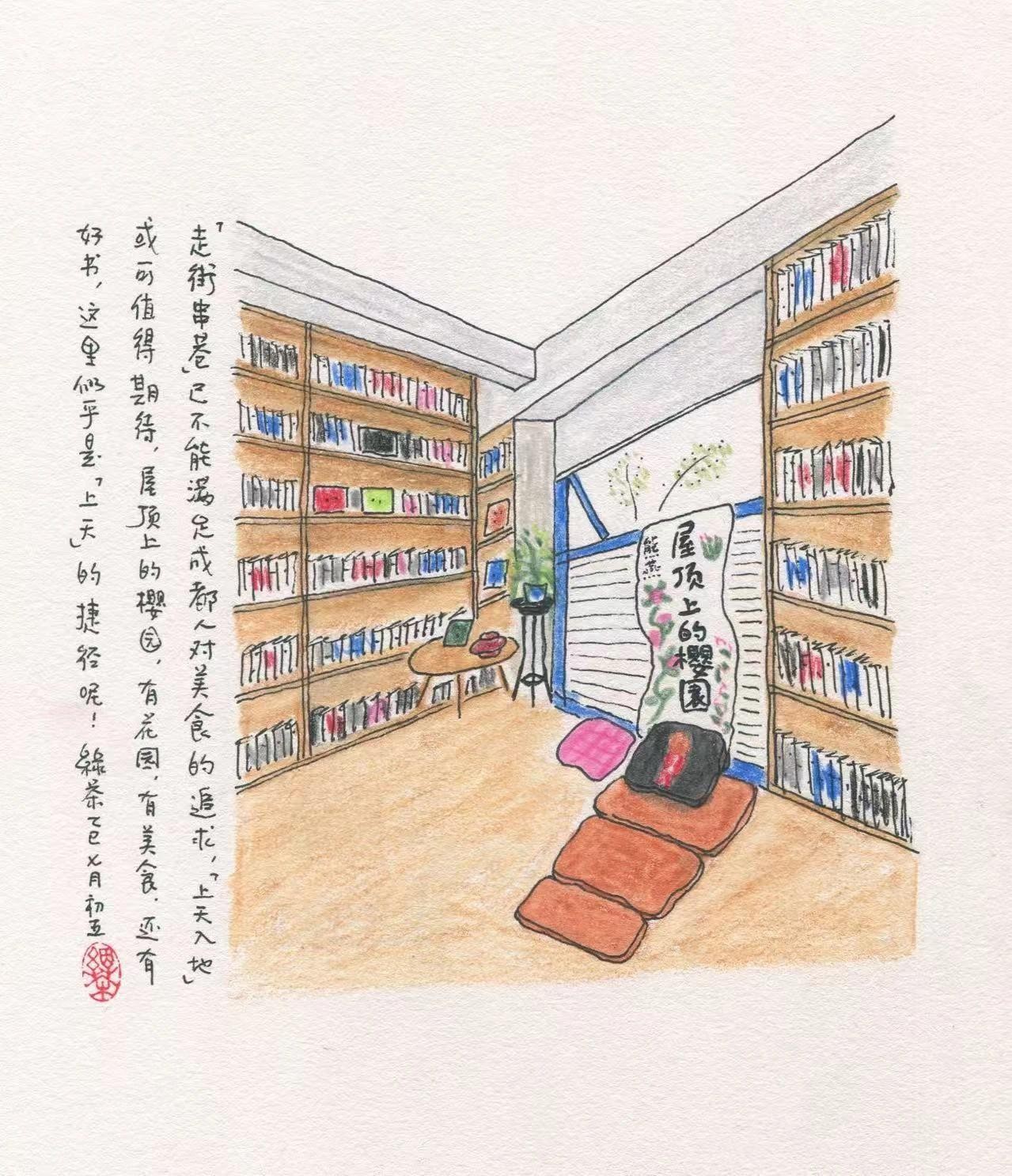

From Guangzhou’s “1200bookshop,” which offers lodging for backpackers, to Chengdu’s “Sakura Garden on the Roof,” where dining and reading blend seamlessly, Fang Xuxiao has visited bookstores nationwide. In his book published late last year, he illustrated 73 distinctive independent bookstores across China.

Fang argues that Chinese cities are becoming increasingly bland and uniform, but locally rooted bookstores reveal each city’s uniqueness. “I remain an idealist—I hope every city brims with diverse, vibrant bookstores.”

Wang Jun of Yiwěi Bookshop hopes society won’t burden bookstores with excessive meaning or光环. “The barrier to opening a bookstore is now about the same as opening a café,” he said. Cultural spaces can take many forms—not just bookstores, but galleries, museums, teahouses, or bars.

“For young people today,” he added, “a decent job and livable environment matter far more than access to cultural spaces. That’s simply more real.”

Chinese Opening Bookstores Abroad? Hoping to Foster Exchange and Immigrant Integration

On Sunday, December 28, Tokyo’s Danlan Street Bookstore wrapped up its final event of 2025—a talk by Oxford social anthropologist Xiang Biao on “Thinking in Chinese and International Exchange,” drawing many local Chinese attendees.

China’s Danlan Street Bookstore opened in Tokyo’s Ginza district in early 2023. That year, four Chinese-language bookstores launched in Tokyo.

Founder Xu Zhiyuan told Lianhe Zaobao in 2024 that after the pandemic, a suitable Ginza location appeared, and he and his partners “acted on impulse—somewhat blindly.”

“At a time when global attitudes toward China have turned abnormal,” Xu said, “I want to show that many Chinese embrace globalization, value diversity, and seek to understand different societies. Bookstores are perfect spaces for intellectual exchange.”

Leilei Xiang, Tokyo Danlan Street’s curator, said in a December interview last year that the store shouldn’t cater only to Chinese expats. “So we host many Japanese-language events. Chinese living in Japan must integrate, and we need more Japanese to understand how to coexist with Chinese. Mutual understanding is absolutely essential.”

Last year, another independent bookstore, Feidi (“Enclave”), opened in Tokyo. Originally founded in Taipei in 2022 by Zhang Jieping—a mainland Chinese native—Feidi has since expanded to Chiang Mai, Thailand, and The Hague, Netherlands.

In 2025, Feidi won Taiwan’s “Shumei Independent Bookstore Award,” which supports indie booksellers. In her award submission video, Zhang said, “Exploring the relationship between newcomers and locals is exactly what Feidi wants to do.”

She explained that in any country, immigrants who overly emphasize their native culture struggle to be accepted. “But when you create a visible space here, immigrants feel more at ease—as if a pier appears in a vast ocean. Its magic is bidirectional: it’s not just a place outsiders can return to, but also one locals can set out from.”

|

Fear of God ESSENTIALS Hoodie Review: Mi26 人气#fashion

Fear of God ESSENTIALS Hoodie Review: Mi26 人气#fashion The Derby of San Francisco Style 300 Cha36 人气#fashion

The Derby of San Francisco Style 300 Cha36 人气#fashion Why the Derby of San Francisco Classic S22 人气#fashion

Why the Derby of San Francisco Classic S22 人气#fashion Romaoss Launches "Rebirth Plan," in Talk12 人气#tech

Romaoss Launches "Rebirth Plan," in Talk12 人气#tech