“MAGA” (Make America Great Again) is often treated in public discourse as a political slogan. But if we place it within the context of America’s industrial and class transformations over the past half-century, it reflects a social reality from one perspective: a large group of families who once entered the middle class through manufacturing now find themselves without a similarly stable and predictable path upward. At its core lies a more fundamental question—can America still provide ordinary people with decent jobs and a dignified standard of living?

This article primarily addresses three questions:

First, how U.S. manufacturing once served as a critical pillar of national power and social structure;

Second, why America systematically lost manufacturing employment and its social function over several decades;

Third, given today’s environment of globalization, geopolitical competition, and technological revolution, should—and can—America bring back some manufacturing capacity domestically? And if manufacturing can no longer fulfill the mission of “rebuilding the middle class,” why is the service sector also ill-equipped to take on this role?

I. The Formation of American Manufacturing Civilization: From a National Market to the “World’s Factory”

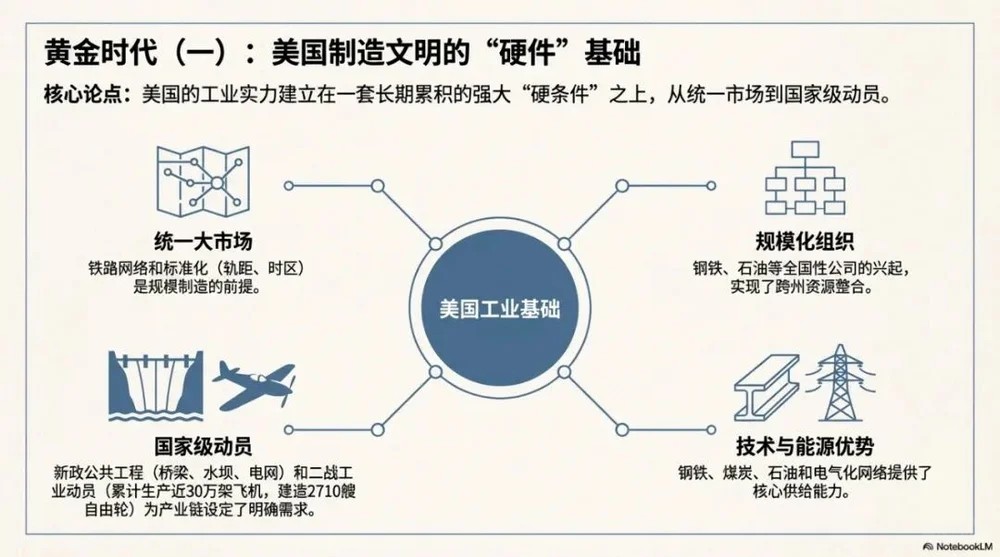

From an institutional and organizational standpoint, early American manufacturing civilization exhibited two key characteristics:

First, enterprises could integrate resources across states and industries. Railroad companies, steel conglomerates, and oil giants were the earliest “national corporations.”

Second, the government was willing, at critical moments, to use public works and military procurement to “set demand,” enabling rapid expansion of industrial chains around clear objectives.

These two factors enabled America’s leap from an agrarian nation to an industrial powerhouse within just a few decades.

The 1938 film The River documented how large-scale, state-led public infrastructure projects tamed nature, built foundational infrastructure, and laid the groundwork for modern manufacturing and industrial civilization.

Two often-overlooked pillars supported the postwar golden age:

One was education and demographics: the GI Bill enabled millions of veterans to enter universities and vocational training systems, rapidly expanding the supply of engineers, skilled workers, and managers.

The other was housing and infrastructure: the Interstate Highway Act of 1956 launched a nationwide highway network that linked suburbanization, the auto industry, petrochemicals, and construction into a decades-long domestic demand “engine.” This provided manufacturing with a stable market and long-term investment expectations.

For several postwar decades, manufacturing and the middle class were bound by an implicit “social contract”: as productivity rose steadily, wages and benefits were broadly shared. Union bargaining, internal corporate promotion ladders, relatively affordable housing and education gave ordinary workers confidence in a predictable future. This contract wasn’t perfect, but it synchronized economic growth with widespread improvements in living standards. Once manufacturing moved offshore, unions weakened, costs rose, and gains concentrated at the top, this social contract began to fray.

America’s rise as a manufacturing power didn’t happen overnight. It rested on a long accumulation of “hard” and “soft” conditions: a unified national market, stable energy and raw materials, continuous technological innovation, scalable corporate structures, and—crucially—the political capacity to mobilize resources decisively during pivotal moments.

In the late 19th century, the railroad network and accompanying standardization (track gauge, time zones, logistics organization) gave America its first truly integrated national market. Manufacturing has always depended on economies of scale: only when raw materials could flow cheaply nationwide and components could be collaboratively produced across regions could enterprises mass-produce complex industrial goods.

In the 20th century, electrification and modern corporate management elevated manufacturing to a new level. Edison-style laboratories weren’t just about invention—they systematized the process from R&D → patents → engineering → mass production → network deployment. The maturation of steel, coal, and oil—the three foundational industries—gave America core capabilities in materials, energy, and transportation.

Post-Depression New Deal public works further tied national construction to industrial development. Bridges, highways, dams, power stations, and electrical grids not only stimulated the economy but also laid the foundation for decades of expansion.

World War II pushed American manufacturing capacity to its limits. To mass-produce military equipment, complex products were broken down into standardized processes, and factories nationwide formed a coordinated network. For example, U.S. military aircraft production surged from fewer than 3,000 units annually in 1939 to nearly 300,000 total by war’s end (commonly cited as ~296,000). The Liberty ship—a standardized cargo vessel—saw 2,710 units built between 1941 and 1945, symbolizing the strategy of “flooding the enemy with industrial output.”

Thus, after the war, America emerged as the center of the global order with overwhelming industrial might, while simultaneously cementing a social structure: manufacturing jobs, unions, welfare systems, and home ownership collectively formed a broad middle class.

An often-overlooked detail of wartime industrial mobilization was its unprecedented push toward standardization. Aircraft, tanks, ships, engines, and radio equipment had their parts specifications unified, allowing factories to switch production rapidly and workers to enter assembly lines after brief training. The state, through uniform contracts and demand signals, turned corporate investment risk into predictable long-term orders. This “certainty-for-capacity” mechanism persisted postwar in defense and aerospace programs.

During the Cold War, the Moon landing program and the military-industrial complex further elevated systems engineering capabilities. It advanced materials, electronics, and precision manufacturing, while reinforcing societal respect for engineering: engineers were culturally seen as those who “lifted the nation to greater heights.” When a society treats engineers as heroes, it becomes more accepting of the risks and uncertainties inherent in grand projects.

The “greatness” of mid-20th-century America wasn’t abstract—it was embodied in factories, assembly lines, ports, railroads, and power grids. Ordinary people gained income and dignity through stable manufacturing jobs.

II. The Age of Fracture: Vietnam, Watergate, and the Rise of the “Error-Averse State”

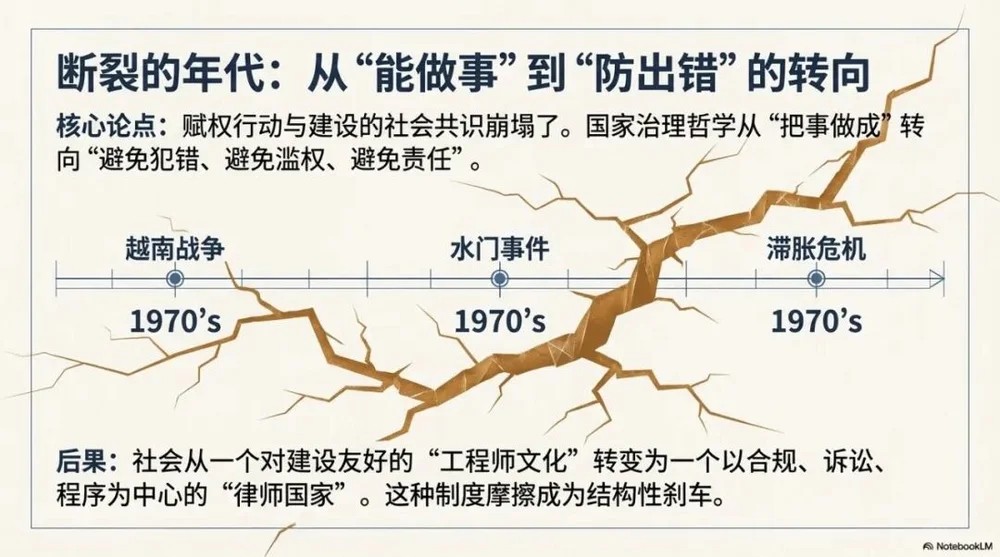

After WWII, America possessed a public culture and institutional framework friendly to construction—tolerant of trial and error, supportive of mobilization, and willing to solve problems through large-scale projects. But after the 1970s, this culture was replaced by a crisis of trust and risk-averse politics. Society increasingly relied on rules, procedures, and litigation to constrain action. The roots of manufacturing’s decline in America lie here.

Vietnam and Watergate didn’t just reshape the political landscape—they shattered the social consensus on whether the state could be entrusted to act. Vietnam exposed the arrogance and opacity of decision-making; Watergate revealed abuse of power and deception. The result: American governance gradually adopted a defensive posture—better slow, better inactive, than to make a mistake. For public works and industrial policy, this was a structural brake.

The 1976 documentary Harlan County, USA captured the intense, protracted struggle between coal miners and capital.

Many essays summarize America’s turning point in one phrase: “from an engineer nation to a lawyer nation.” A more accurate description is this: America was never ruled by engineers, but it was long a nation friendly to action and construction. After the 1970s, it solidified into a “lawyer nation” centered on compliance, litigation, procedure, and liability fragmentation. The key shift wasn’t in the number of engineers, but in the erosion of societal trust in the legitimacy of action itself.

The Vietnam War first shattered the belief that “government action is inherently correct.” Television brought war into living rooms, prompting systemic public skepticism toward official judgment and mobilization. Watergate then destroyed the moral legitimacy of power: presidential lies, cover-ups, and abuses bred instinctive distrust. The energy crisis and stagflation exposed the fragility of the industrial system in terms of cost and supply.

These three shocks together triggered not just policy adjustments, but a philosophical shift in governance: the state no longer prioritized “getting things done,” but emphasized “avoiding errors, abuse, pollution, and liability.” Regulatory systems, environmental reviews, public hearings, and judicial appeals—while historically justified—collectively created massive institutional friction. When a society elevates “error prevention” as its highest value, its speed and coordination in public works and industrial development inevitably decline.

III. The Rapid Decline of U.S. Manufacturing: The Convergence of Three Forces

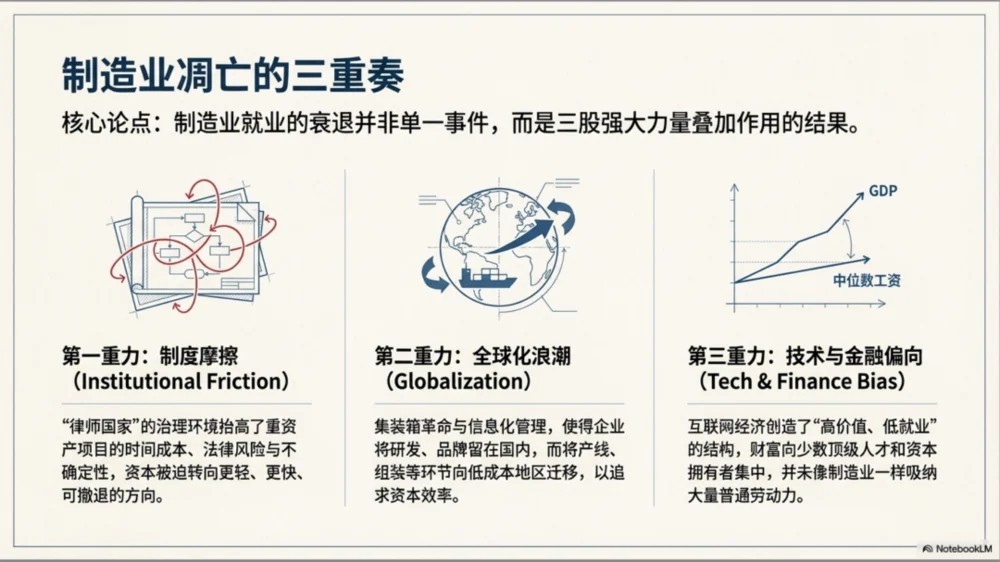

The long-term decline in U.S. manufacturing employment cannot be explained by a single cause. Rather, three forces converged simultaneously: rising institutional friction (action constrained by procedure), globalization naturally shifting manufacturing to low-cost regions, and the prosperity of the internet and financialization concentrating gains among a small group of high-skilled individuals, leaving the “manufacturing middle class” without a viable replacement industry.

1) Institutional Friction: The Cost and Time of the “Lawyer Nation”

This friction isn’t just about “slower approvals”—it reshapes organizational behavior: firms prefer investing in mobile, retractable, quickly recoverable assets; local governments favor politically lower-risk projects; officials delegate decision-making to avoid personal accountability. Over time, society enters a state where “no one is responsible for pushing forward, but many can block.”

Manufacturing hates uncertainty—especially heavy-asset projects like factories, energy, and infrastructure. When approval timelines stretch, litigation risks loom, and community veto power grows, capital expenditures shift toward lighter, faster, more retractable options. America’s high-friction governance environment since the 1970s has made “building” increasingly costly, while “not building” becomes cheaper.

This affects not only public works but also private investment expectations: when a factory takes years to navigate permits, environmental reviews, and legal uncertainty, capital naturally seeks more predictable locations.

2) The Tide of Globalization: Manufacturing Naturally Migrates to Low-Cost Regions

Globalization is a system of technological and organizational conditions:

Containerization drastically reduced shipping costs;

Information systems enabled cross-border coordination;

Multinational corporations fragmented R&D, design, components, and assembly, sourcing each globally for optimal efficiency.

Under this system, America retained upstream control of value chains and finance, while overseas regions absorbed manufacturing employment. This was “efficient” for corporate profits and consumer prices—but caused long-term hemorrhaging of America’s class structure.

American firms outsourced manufacturing for another practical reason: manufacturing profit margins have long lagged behind software, finance, and platform businesses, while capital markets pressured management with quarterly earnings and stock prices. Thus, firms naturally treated manufacturing as a replaceable cost center and brands/channels as profit centers—a logic especially pronounced after the 1990s.

Offshoring wasn’t a conspiracy—it was the natural outcome of global capital efficiency. Japan and the “Four Asian Tigers” industrialized between the 1960s–80s, followed by Southeast Asia and Mexico absorbing mid-to-low-end manufacturing. After the 1990s, container shipping, digital supply chain management, and trade frameworks (e.g., NAFTA in 1994, China’s WTO accession in 2001) accelerated the concentration of global manufacturing in lower-cost regions.

In this context, U.S. firms moved production, components, and assembly overseas while keeping R&D, branding, finance, and market control at home. Manufacturing employment hollowed out, yet the U.S. economy appeared to grow—because profits and high-value activities remained.

3) The Bias of Technology and Finance: A Richer Nation, But Not Necessarily Better Off for Ordinary People

As globalization reduced manufacturing jobs, the internet redistributed the “fruits of growth.” The digital economy generated immense wealth density—but this wealth doesn’t automatically diffuse to the broader workforce. Tech firms create higher market value with fewer employees; finance amplifies returns through asset prices and leverage; meanwhile, low-skill service wages struggle to keep pace with living costs. This explains an apparent paradox: macroeconomic stagnation hasn’t occurred, yet bottom layer and middle-class security has declined.

Since the 1990s, America has ridden waves of internet and digital technology. The tech sector created enormous market value and profits—but with a “high-value, low-employment” structure: a small elite of talent and capital owners captured most gains, unlike postwar manufacturing, which absorbed vast numbers of ordinary workers and built a thick middle layer.

More critically, the digital economy is geographically concentrated. Wealth and high-paying jobs cluster in a few superstar cities, leaving inland regions—deprived of industrial anchors—unable to benefit from the new economy. This fuels a “urban prosperity vs. small-town decline” divide, which often manifests politically not as sudden extremism, but as divergent lived economic realities.

Simultaneously, financialization and the doctrine of “shareholder value maximization” prioritized short-term returns. Stock buybacks, merger arbitrage, and light-asset outsourcing became mainstream strategies, while heavy-asset manufacturing and long-term skill development grew unattractive on corporate balance sheets. Macroscopically, U.S. per capita GDP rose steadily alongside tech and service prosperity; microscopically, traditional working-class wages, benefits, and community stability declined.

IV. Putting Numbers on the Table: Output, Employment, and the “Illusion of Disappearing Manufacturing”

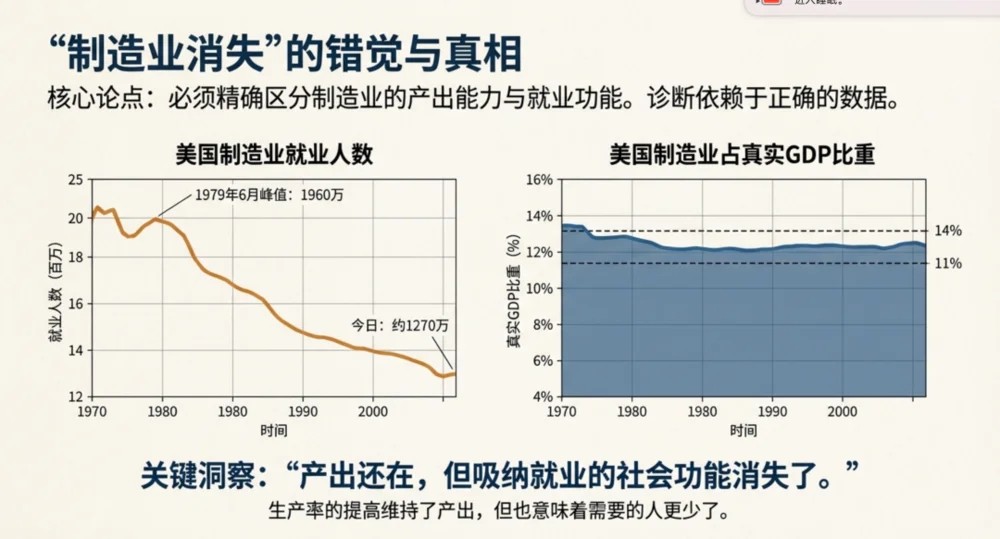

Data interpretation requires distinguishing between “nominal share” and “real share.” Manufacturing’s nominal GDP share declined partly because manufactured goods prices rose slower (or even fell) relative to services like healthcare, education, and housing—making services appear larger in nominal terms. In real (inflation-adjusted) terms, manufacturing output hasn’t shrunk proportionally.

On output: using nominal measures, a Chicago Fed study noted manufacturing accounted for ~27% of U.S. nominal GDP in 1950, falling to 12.1% by 2007. But in real terms, St. Louis Fed analysis shows manufacturing’s share of real GDP has remained relatively stable (~11–14%) over decades. Employment declines stem more from productivity gains and global specialization. In other words, America hasn’t stopped manufacturing—it’s producing the same or more real output with fewer workers, while employment and community economies shifted to services.

On employment: BLS data shows U.S. manufacturing employment peaked at 19.6 million in June 1979, falling to 12.8 million by June 2019—a ~35% drop. By September 2025, it stood at ~12.72 million (FRED/BLS series). Absolute manufacturing jobs shrank significantly, but more crucially, its share of total employment fell from postwar highs to near single digits.

Together, these figures yield a precise conclusion: manufacturing hasn’t “disappeared” from America—its real output capacity remains—but it no longer fulfills its former social function of mass labor absorption.

The drop from 19.6 million to 12.7 million means ~7 million fewer manufacturing jobs. Meanwhile, total U.S. employment grew, with service jobs expanding—so manufacturing’s employment share fell faster. For ordinary people, the key isn’t how much America still produces, but whether the career ladder to the middle class still exists.

This explains why macro statistics show continued U.S. prosperity, yet ordinary people feel less secure about the future. Real output can be sustained via productivity—but higher productivity often means fewer workers are needed. Manufacturing’s historical political and social significance lay in its ability to diffuse growth nationwide through mass employment—not just producing goods, but providing stable class pathways and community order. When this diffusion mechanism vanished, growth concentrated in a few sectors and cities, fueling class and regional polarization.

V. If Manufacturing Doesn’t Return, Can Services Sustain the Middle Class?

Whether services can sustain the middle class isn’t a moral question, but a structural one: it must simultaneously satisfy three conditions—sufficient job volume, decent pay, and clear career ladders. Manufacturing achieved all three in the 20th century; the service sector as a whole struggles to do so—especially in a society like America’s, where healthcare, education, and housing costs are extremely high, making low-wage service jobs insufficient for a “decent life.”

This is the central question America must confront: if we’re deeply pessimistic about manufacturing’s return—even if key sectors are rebuilt, they likely won’t absorb tens of millions of workers as in 1950–1970—can services become the anchor of industrial transition?

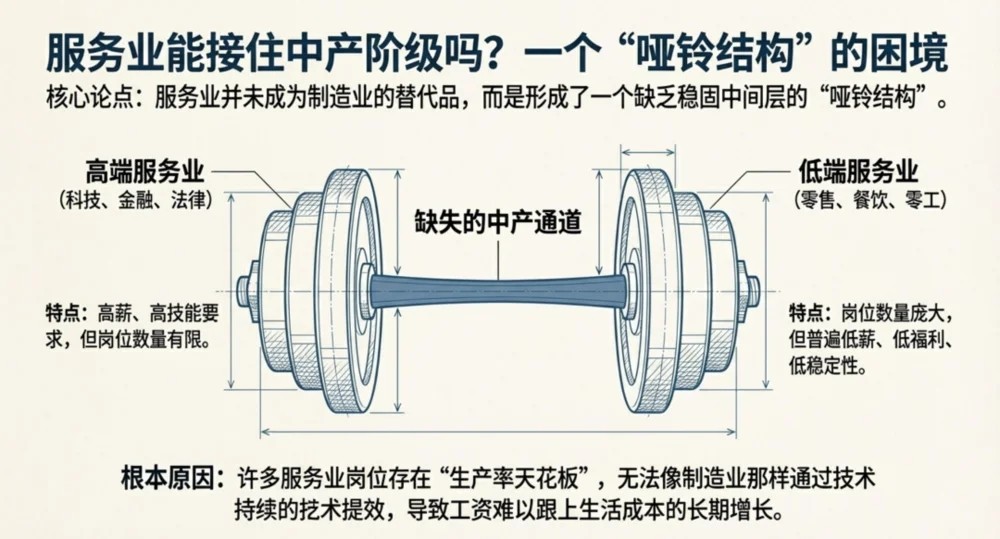

Intuitively, it seems possible. America is now a quintessential service economy, with high service employment and advanced tech, finance, healthcare, and education. But disaggregating services reveals its inability to replicate manufacturing’s former “social function.”

1) Services Have a “Dumbbell Structure”: Either Too High-Skilled or Too Low-Paid

High-end services (tech, finance, law, specialized healthcare) create immense value but demand elite education, skills, and urban agglomeration—offering limited jobs incapable of absorbing the vast workforce displaced from manufacturing.

Low-end services (retail, food, hospitality, cleaning, delivery, warehousing) offer abundant jobs but typically feature low wages, poor benefits, and instability—insufficient to support America’s high cost of living (healthcare, housing, education, insurance). The middle path—large-scale, decently paid, trainable, with clear advancement—is extremely narrow.

2) Productivity Ceiling: Services Struggle to Boost Efficiency Like Manufacturing

Manufacturing continuously raises labor productivity via automation, process improvement, and scale—providing a long-term basis for wage growth. Many service jobs (caregiving, education, food service, childcare) are inherently hard to scale efficiently: you can’t multiply hourly output via machines like on an assembly line. Thus, wages in these sectors struggle to keep pace with societal cost increases.

3) Geographic Distribution: Service Prosperity Is Concentrated, Failing to Revive the “Rust Belt”

Manufacturing could anchor inland cities and towns, supporting housing, schools, tax bases, and community stability. High-end services cluster in coastal megacities; low-end services are ubiquitous but lack the wages and tax base to replace a major factory’s local economic impact. Thus, even with national GDP growth, geographic imbalances worsen, fueling inland disillusionment and anger.

4) Career Ladders: Services Lack Manufacturing’s “Predictable Advancement”

The stability of the blue-collar middle class wasn’t just about wages—it was about “career ladders”: apprentice → skilled worker → senior technician → team leader → shop floor supervisor → plant management. Most service jobs lack comparable skill accumulation and promotion paths, making individual effort hard to convert into long-term security.

Therefore, if manufacturing doesn’t return and services can’t reproduce the middle class, America faces a structural vacuum: masses of ordinary workers stuck in low-wage, unstable jobs, growing ever farther from a small elite of talent and capital owners. Political left-right conflicts easily morph into class antagonism under these conditions, raising social instability risks.

This also explains why economically “correct” choices often prove politically unsustainable: offshoring lowers costs and boosts efficiency for firms and consumers, but deprives millions of a dignified path. Long-term, disappointment and anger coalesce into social forces driving anti-globalization, anti-elitism, and political polarization. Surface-level partisan conflict may give way to deeper class divisions, increasing societal conflict risks.

VI. From “Can We?” to “Should We?”: Does America Need to Regain Critical Manufacturing Capacity?

Thus, America’s current “reindustrialization” has two tracks: one focused on national capability—ensuring security and resilience in critical supply chains; the other on social structure—ensuring ordinary people can share in growth. Politically, these merge into a single task: bringing jobs back. But policy design requires different tools: the former leans toward industrial security and public procurement; the latter toward rebuilding housing, education, healthcare, and skills systems.

If the world remained in a credible, controllable, rule-based global order, America could theoretically remain an innovation-, finance-, and service-centered nation, outsourcing manufacturing to trusted partners and focusing on high-value segments. This vision seemed plausible during certain 1990–2010 phases: U.S. growth continued, tech firms rose, consumer prices fell, and ordinary people enjoyed cheaper global goods.

But this vision rests on two premises:

First, global supply chains remain stable and immune to geopolitical shocks;

Second, America possesses a domestic alternative industry capable of absorbing ordinary labor at scale and providing decent incomes.

Reality increasingly undermines both. Geopolitical supply chain risks are rising, making full outsourcing untenable in critical areas (semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, key materials, defense manufacturing, grid/energy equipment). Simultaneously, America’s “spiky” industrial structure leaves most ordinary people unable to share in growth.

Hence, today’s talk of “reindustrialization” is less about nostalgia and more about rebuilding irreplaceable national capabilities: avoiding chokepoints in critical sectors, ensuring self-sufficiency during crises, and retaining a manufacturing base for technological competition. Equally important is answering a harder question: if reshored manufacturing can’t rebuild a massive middle class, what will sustain ordinary people’s decent lives?

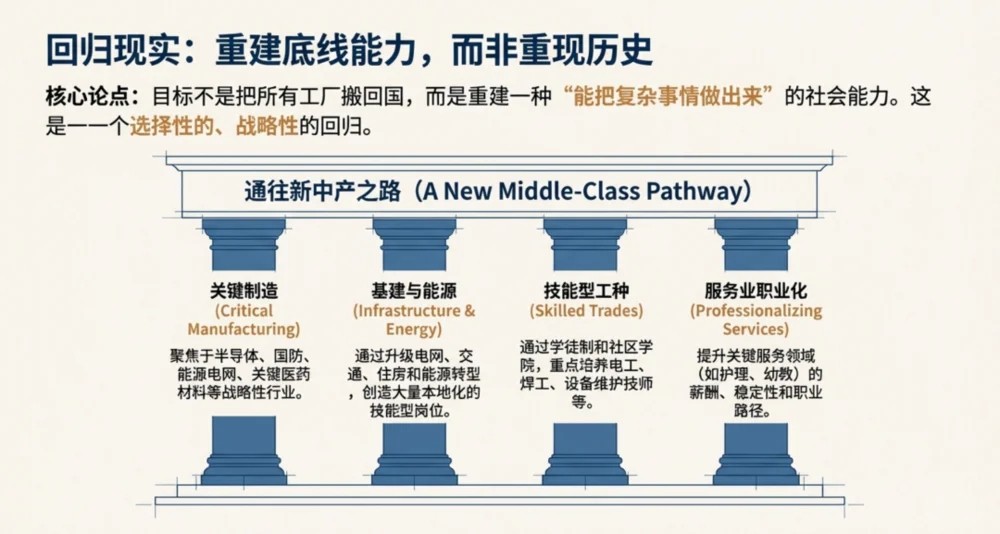

VII. A Realistic Path Forward: Not Returning to the Past, But Rebuilding Baseline Capabilities

This shapes realistic expectations for “manufacturing return”: America is unlikely to restore the era when manufacturing employed one-third of the workforce, but fully abandoning manufacturing is equally unrealistic. A more feasible goal is building sustainable domestic capacity and supplier networks in a few critical industries, while using infrastructure renewal, energy transition, and skilled trades expansion to offer stable careers to broader populations.

In other words, America doesn’t need to bring all factories home—it needs to rebuild the societal capacity to “get complex things done”: launch projects, deliver on schedule, cultivate skills, and let ordinary people earn dignity through labor. Manufacturing is merely the most emblematic—and hardest—component.

Bringing all manufacturing back to America is nearly impossible. Costs, supply chains, labor structures, and institutional friction persist; global specialization is too deep to reverse. A more viable path is “selective reshoring”: relocating domestically or among trusted partners only those segments vital to national security, core technologies, and long-term competitiveness.

This implies policy should focus on verifiable goals:

First, replace “endless delays” in permitting with “clear timelines.” Maintain environmental standards, but shift procedures from sequential to parallel and make accountability traceable. Manufacturing needs certainty.

Second, rebuild the skills pipeline. Manufacturing revival depends not on subsidies, but on skilled workers, engineers, site managers, and supplier networks. Apprenticeships, community colleges, retraining programs, and immigration policy must align with “industrial skills shortages.”

Third, use public procurement—defense, energy projects—to pull domestic supply chains. Historically, America’s most successful manufacturing expansions stemmed from public-sector stability in standards, demand, and long-term contracts.

Fourth, treat “housing, healthcare, and education costs” as part of industrial policy. Without affordable living costs, even high wages get eroded, and ordinary people can’t build security.

Combined, these policies may not restore 1950s-level manufacturing shares, but could forge a new stability: critical manufacturing + infrastructure renewal + skilled trades (electricians, welders, maintenance, construction, energy retrofitting) jointly providing scalable paths to decent employment.

Returning to the opening question: Can MAGA be realized? If interpreted as “returning America to the 1950s,” the answer is likely no. But if understood as “restoring a social structure where ordinary people can live decently,” the outlook isn’t entirely bleak.

But this requires America to undertake painful rebalancing: preserving rule of law and rights protection while restoring certainty in action and construction; embracing tech and innovation while ensuring most people have accessible, upward economic paths.

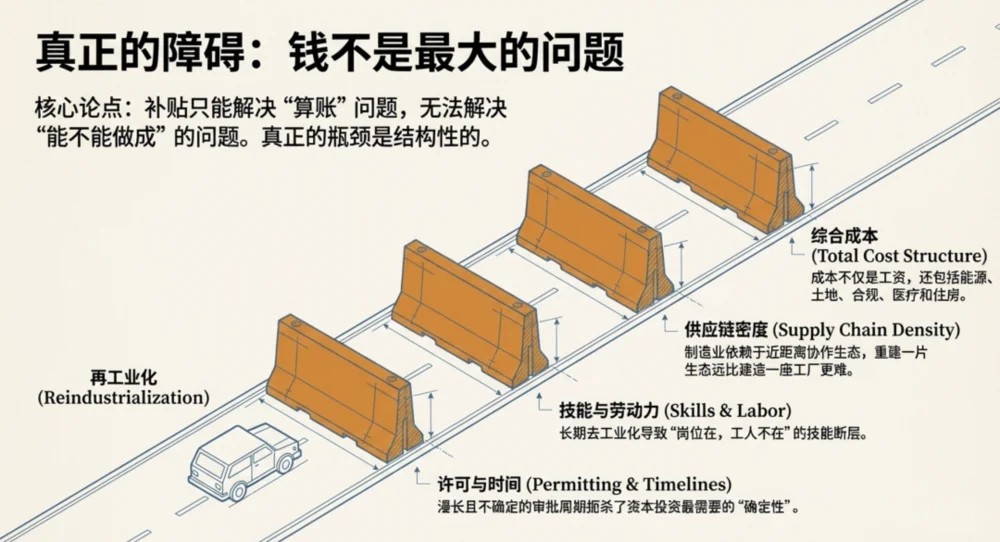

VIII. Real Obstacles to Reindustrialization: Money Isn’t the Biggest Problem

Viewing “manufacturing return” as a simple subsidy race underestimates America’s structural barriers. Subsidies matter—they address “can the math work?”—but not “can it actually be done?” For manufacturing, true bottlenecks lie in four areas: permitting/time, skills/labor, supply chain density, and cost structure.

Permitting and time shape expectations. For capital-intensive factories, the biggest cost is often time itself. Each delayed year amplifies financing costs, opportunity costs, and uncertainty. Recent U.S. efforts to reshore semiconductors and clean energy manufacturing frequently cite long project cycles and high coordination costs as key hurdles. Even without lowering environmental standards, shifting procedures from “endless” to “time-bound” directly determines whether capital stays committed.

Second is skills and labor. Manufacturing isn’t just installing machines—it relies on a full skills pyramid: technicians, maintenance staff, process engineers, quality control, site supervisors. After decades of deindustrialization, America faces a “jobs exist, workers don’t” mismatch: too few people willing and able to work in factories, long training cycles, high turnover. Without on-the-ground capability, subsidies may just fund expensive experiments.

Third is supply chain density. Manufacturing efficiency comes from “proximity collaboration”: molds, chemicals, components, logistics, repairs, subcontracting must form a network within a manageable radius. America has lost this density in many sectors, forcing even completed factories to source globally—again inflating costs and timelines. Supply chains aren’t single plants—they’re ecosystems.

Fourth is cost structure. U.S. manufacturing costs stem not just from wages, but from energy, land, compliance, insurance, healthcare, and housing. For standardized manufacturing, these differences often make large-scale reshoring impractical. Realistic opportunities lie in “high-value, high-security, delivery/reliability-sensitive” sectors: advanced semiconductors, select defense/aerospace, critical grid equipment, key pharmaceuticals/materials, and energy-transition-related advanced equipment.

Another overlooked reality: even if some manufacturing returns, it won’t solve all employment issues—modern manufacturing is increasingly automated. Advanced factories need more engineers and maintenance staff, but fewer direct production workers. Thus, successful “reindustrialization” may restore capacity and security, not 20th-century job volumes. America must simultaneously develop other employment-diffusing sectors: infrastructure, housing construction, energy retrofitting, and professionalization of skilled service jobs.

IX. Tariffs, Subsidies, and “Manufacturing Nostalgia”: Why Simple Policies Often Fail

In American political discourse, “bringing factories back” is often reduced to tariffs or subsidies. But tariffs are blunt price tools: they raise import costs to create space for domestic production. The problem? Tariffs also increase intermediate input costs, squeezing domestic competitiveness, and pass inflation to consumers. More importantly, tariffs don’t automatically generate skilled workers, supply chains, or delivery capacity. They change prices, not capabilities.

Subsidies resemble industrial policy: using fiscal tools to make uneconomic projects viable. But subsidies have limits—if politicized, they fragment into symbolic gestures; without exit mechanisms, they breed dependency. A more realistic approach ties subsidies to verifiable capability-building: training systems, local supplier ratios, delivery milestones, quality/safety metrics. Otherwise, subsidies may leave only expensive buildings, not sustainable industrial networks.

Thus, America’s real challenge isn’t “whether to support manufacturing,” but what to support, how much, and how to convert support into long-term capability—not one-off political theater.

X. If Manufacturing Can’t Rebuild a “Mass Middle Class,” What Can Sustain Ordinary Americans’ Decent Lives?

While services overall can’t replace manufacturing in “middle-class reproduction,” America isn’t forced to choose between “manufacturing return” and “social fracture.” A more realistic path shifts the source of “decent work” from a single industry to a mutually reinforcing portfolio.

First: infrastructure and housing. Many U.S. cities face housing shortages, aging transit, and outdated grids/water systems. Infrastructure renewal creates abundant skilled jobs (electricians, welders, maintenance, construction management) and lowers living costs via better housing/commuting—indirectly boosting real incomes. Its social impact rivals industry itself.

Second: energy transition and industrial services. Grid upgrades, energy storage, EV charging networks, and building retrofits require vast on-site skills and local crews. Unlike the internet’s “high-value, low-employment” model, this offers nationwide diffusable skilled employment. The key is designing policies that turn these into long-term careers, not short-term projects.

Third: redesigning care and education services. Traditional care jobs suffer from low pay and high turnover due to payment systems, public underinvestment, and weak certification. If America shifts public spending from “after-the-fact subsidies” to “front-end professionalization,” raising pay and stability in caregiving, early education, and community health, it could create quasi-middle-class service career paths. The hurdle is fiscal and political consensus.

Fourth: limited expansion of “critical manufacturing + domestic supply chains.” Even if manufacturing can’t return to employing one-third of workers, America still needs deliverable capacity in key areas. It provides high-quality jobs and anchors technological/industrial capability.

In short, future American stability won’t rely on a single industry, but on a combination: baseline manufacturing capability + infrastructure/energy renewal + skilled trades expansion + service sector professionalization. The difficulty lies in turning fragmented projects into continuous career paths and short-term policies into long-term institutions.

XI. Returning to MAGA: The Real Test Is “Making Most People Believe in the Future Again”

If MAGA means returning to the 1950s, it’s likely unattainable nostalgia. But if it means restoring a social structure where ordinary people gain dignity through labor, communities stabilize, and upward mobility becomes visible again—it becomes a serious, realistic governance challenge.

Here, manufacturing’s value isn’t its output, but the “predictable life path” it once offered. When that path vanishes, disappointment and anger coalesce into social forces that manifest politically as polarization and conflict. To reduce this risk, America must address not just industrial policy, but living costs, skills systems, housing supply, public services, and local economic sustainability.

America can certainly maintain macro growth—tech, finance, and professional services remain strong. But national stability depends on whether growth translates into widespread security. If gains accrue only to a few, even soaring GDP won’t prevent social fracture.

Thus, assessing America’s manufacturing return shouldn’t focus solely on factory counts, but on integration with broader institutional reforms: Can permitting become predictable? Can skills systems be rebuilt? Can housing/healthcare costs be alleviated? Can services be partially professionalized?

Only when these pieces improve together can America regain future-oriented stability without reverting to the past.

Metrics for “being on the right track” also need updating: rather than fixating on restoring historical manufacturing employment shares, focus on stability-oriented outcomes—can median household income outpace living costs? Can housing/healthcare expenses as a share of income decline? Can skilled trades (technicians, electricians, maintenance, construction management) form replicable career ladders? Are inland regions seeing sustained tax base and employment improvements? Only when these improve will ordinary people believe in the future—not just witness factory ribbon-cuttings.

This is a slow endeavor. If America truly seeks stability without retracing its steps, it must repair both its “capacity to build” and its “structure for broad benefit.” Otherwise, even the loudest slogans will echo only as emotion.

Revised Draft – December 2025

Data and Sources:

1) Peak and long-term decline of U.S. manufacturing employment: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Beyond the Numbers, “Forty years of falling manufacturing employment” (2020-11-20), and FRED/BLS series CEU3000000001 (updated to 2025-09).

2) Manufacturing share of nominal GDP: Chicago Fed Midwest Economy Blog, “Is U.S. Manufacturing Disappearing?” (citing 27% in 1950, 12.1% in 2007).

3) Manufacturing share of real GDP range: St. Louis Fed On the Economy, “Is U.S. Manufacturing Really Declining?” (2017-04-11, citing ~11.3%–13.6% range since the 1940s).

4) WWII aircraft and Liberty ship data: Total U.S. aircraft production ~296,000 units (common statistical reference from “United States aircraft production during World War II” citing Army Air Forces Statistical Digest, World War II); 2,710 Liberty ships built 1941–1945, per U.S. National Park Service educational materials and Liberty ship data compilations.

|