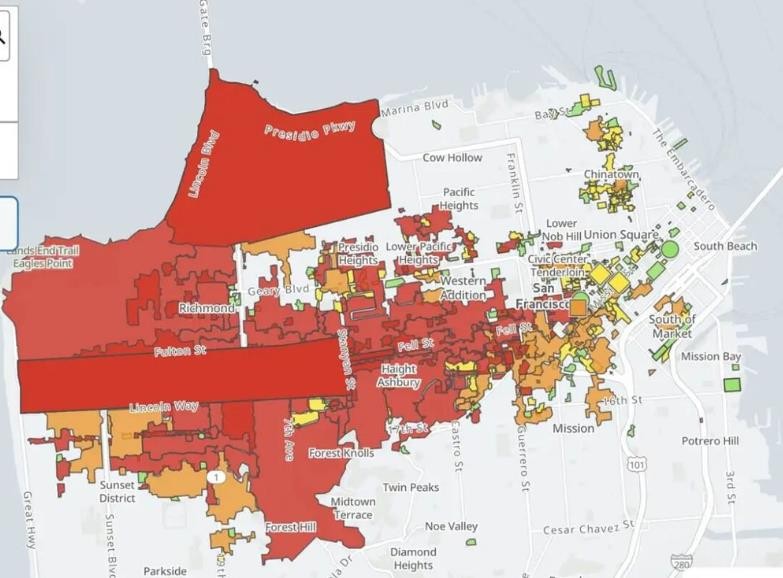

On the evening of December 21 local time, a large-scale power outage hit San Francisco, USA.

But who would have thought that besides disrupting the daily lives of 130,000 residents, the outage would even paralyze the city’s traffic!

As traffic lights completely went out, fleets of Waymo’s Robotaxi autonomous taxis were left stranded, completely blocking intersections.

Worse still, there were no safety drivers on board...

This meant they couldn’t move themselves to safe areas on their own, and had to wait for remote operators to take control one by one or for on-site rescue.

However, the rescuers were often blocked at the next intersection by another group of Robotaxis.

Autonomous driving and Robotaxis have long been controversial locally. This failure at a critical moment only added fuel to the fire, further alienating the public.

At this point, Elon Musk—who has always looked down on Waymo—quickly jumped in to rub salt in the wound:

“The power outage had no impact on Tesla’s Robotaxi operations.”

The stranded Waymo vehicles and Tesla’s unimpeded ones formed a stark contrast—as the saying goes, “One shines brighter by comparison.”

For this reason, some American netizens commented: “If I were Waymo, I’d just call it quits! Tesla will surely dominate the autonomous driving industry from now on—what’s the point of continuing?”

However, others reject the logic that “Tesla didn’t stall = FSD technology is more advanced.”

After all, autonomous driving needs to handle countless scenarios. A fair and objective evaluation must consider response strategies across various complex situations, with power outages being just one of them.

Nevertheless, it is an undeniable fact that Waymo’s Robotaxis have shortcomings and flaws.

Let’s first explain why Waymo vehicles collectively stalled at intersections.

Waymo Drive, an out-of-the-box L4 autonomous driving system, belongs to the typical “map-heavy, rule-heavy” school.

Its operation process is: draw high-precision maps → perceive real-time information through multi-redundancy systems → make predictions based on existing rules → plan and execute routes.

Honed by over 100 million miles of real-road data, Waymo Drive can be considered relatively mature.

For example, some netizens questioned that Waymo failed to understand basic road rules, leading to “confusion” at intersections during the outage—but this is actually unfair.

As highlighted in the regulations, when traffic signals are inoperable, all directions must stop first and proceed only after confirming safety.

This is what many refer to as the American “four-way stop” rule, with slightly complex right-of-way priorities—

Vehicles arriving first go first; straight/right-turning vehicles have priority over left-turning ones. If vehicles from all four directions arrive simultaneously and all need to turn left, drivers coordinate through gestures, eye contact, or other forms of human communication.

Waymo Drive has learned this rule but failed to handle it properly.

It’s like a student learning a formula in class, only to face a complex array derived from that formula in the exam—suddenly increasing the difficulty of solving the problem.

Waymo’s spokesperson offered a similar explanation:

While technically capable of handling signal failures, the “major failure of utility infrastructure” combined with the resulting traffic chaos forced vehicles to stay longer for safety reasons.

In other words, San Francisco that night resembled a large-scale game of the “dark forest.” Following the rule of stopping first and proceeding only after assessing conditions, Waymo vehicles stopped at intersections but couldn’t confirm 100% safety to proceed, so they had no choice but to remain stationary.

To outsiders, this looked like Waymo had crashed.

Unfortunately, as the number of “crashed” vehicles surged, cloud-based remote operators could only assist with a portion of them—their response speed couldn’t keep up with the new stalled vehicles. Coupled with network outages caused by the power failure, roads were completely blocked.

Musk’s “trash-talking” was indeed well-founded.

According to netizens in the comment section, even during the outage, Tesla’s FSD didn’t crash at unlit intersections and performed on par with or even better than “the best human drivers.”

This is intriguing.

Waymo, which began testing Robotaxis earliest, has long been regarded as the global leader in L4 autonomous driving, holding the top spot in technical capabilities.

Tesla, by contrast, only officially launched its Robotaxi pilot program in June this year. It has only removed safety drivers from some operating areas in Austin, Texas, making it a latecomer in the Robotaxi field.

So why did Waymo perform worse than Tesla in an extreme scenario like a power outage?

In the editor’s opinion, there are two fundamental reasons.

First, flaws in the data from Waymo’s massive road test mileage.

Or more bluntly, logical flaws in the data collection process.

Waymo has accumulated two types of mileage data: simulated driving data (generating numerous virtual worlds mimicking real road conditions for Robotaxis to practice responses)

and real-road operational mileage (exceeding 100 million miles and growing rapidly with 450,000 weekly Robotaxi trips).

Theoretically, Waymo can take extreme scenarios encountered on real roads, test them repeatedly in simulated environments until finding the optimal response, and then apply it to the real world.

However, all data accumulated by Waymo is based on the premise that urban traffic signals are functioning and traffic order is basically maintained.

Scenarios like zombie outbreaks, airstrikes/ gunfights, or signal outages caused by power failures were never considered by Waymo.

Thus, once rules fail and even human drivers have to communicate through gestures and eye contact, Waymo—positioned as L4 and prioritizing 100% safety—inevitably refrains from actively participating in such chaos, leading to inevitable crashes.

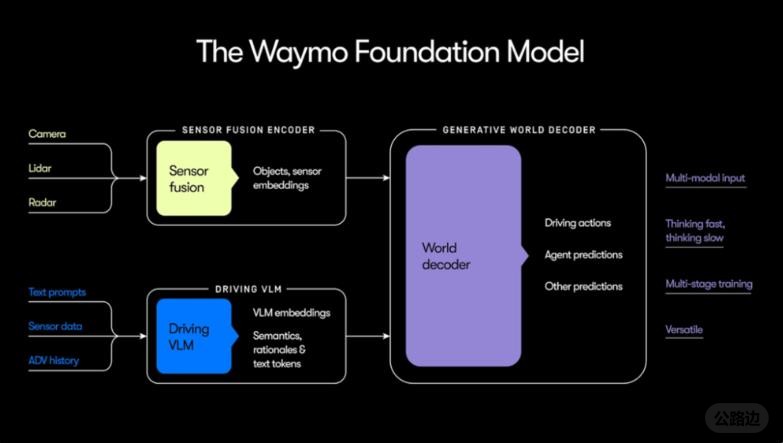

Second, differences in autonomous driving technical routes between Waymo and Tesla.

Waymo has chosen a multi-sensor fusion solution equipped with lidar.

Instead of fully betting on end-to-end large models, it adopts a hybrid design combining world models with end-to-end learning, aiming to provide robust safety backup capabilities.

Tesla’s route is more familiar: it firmly supports the pure vision solution. And since FSD V12, Tesla has been the leading player in integrating end-to-end large models into autonomous driving.

The biggest difference between multi-sensor fusion and pure vision solutions is not the presence of lidar, but the underlying perception algorithm logic.

Additional lidar (and millimeter-wave radar) means more perception sources and higher-level safeguards.

However, this places higher demands on algorithms and computing power—

An extreme example: lidar detects a large transparent plastic bag ahead, requiring braking; but the camera still clearly sees the road ahead, indicating it’s safe to continue.

Human drivers can naturally handle this with experience. But when data conflicts, which should the algorithm trust? Moreover, if computing power is insufficient, by the time the system reacts from hesitation, it’s too late for the vehicle to act.

Therefore, all L4 autonomous driving companies must invest heavily in algorithms and computing power.

From this perspective, Tesla’s pure vision route processes less perception information and has a simpler decision-making process.

FSD’s end-to-end large model can adapt to situations based on camera data without relying on high-precision maps or coded rules, making better decisions than human drivers—

Even for scenarios it has never been trained on in simulations.

Nevertheless, the power outage test has taught Waymo a harsh lesson.

On December 23, Waymo announced an update to its Robotaxi autonomous driving system to improve response to power outages. Additionally, Waymo stated it would learn from the outage to revise emergency response protocols.

Admittedly, while Waymo embarrassed itself globally, it also collected valuable data on extreme scenarios—so it’s not a total loss.

However, the cost of this gain is indeed substantial.

Final Thoughts

Musk’s retort to Waymo also reflects the intensifying competition in the Robotaxi race.

Currently, Waymo operates a fleet of 2,500 Robotaxis across 5 major U.S. cities.

Next year, Waymo plans further expansion: adding 12 new operating cities (including London, its first overseas location) and 12 new test cities to pave the way for future operations.

Meanwhile, Tesla’s “true driverless” vehicles (without safety drivers) will expand from around 150 in Austin, Texas, to an expected 1,000 next year with the mass production of the Cybercab.

After all, in Musk’s view, autonomous driving is one of Tesla’s most important future growth drivers and will undoubtedly be a top priority for him.

The San Francisco power outage serves as a wake-up call for both Waymo and Tesla: they must prioritize extreme scenarios that are rare but have massive social impacts when they occur.

For L4 autonomous driving companies like Waymo, balancing aggressiveness (efficiency) and conservatism (safety) will become even more challenging.

The editor believes many people hope Robotaxis will follow traffic rules to ensure safety when roads are clear, but also use a bit of “ingenuity” to bypass rules and prioritize efficiency when conditions are poor.

However, expecting Robotaxis to accurately understand every human driving preference while winning interactions with various road users is as unrealistic as “expecting humans to remain rational forever.”

As for completely eliminating traffic accidents—perhaps we can only hope for fully automated traffic under vehicle-road coordination?

Regardless, the debate between the incremental approach (from L2 to L4) and the “big bang” approach (achieving L4 directly) seems to be approaching a conclusion.

|