In early last year, Groq emerged, challenging both NVIDIA and Google simultaneously. By the end of this year, Google’s TPUs had rewritten the AI narrative, and Jensen Huang’s response was to bring the Groq team—who developed the first - generation TPU—back into the fold.

TPUs Cannot Be Stopped: Jensen Huang Spends $20 Billion to Buy Out the Former Core Team

This is a typical talent acquisition. NVIDIA paid Groq $20 billion to obtain a non - exclusive license for its inference technology. Groq founder and CEO Jonathan Ross, President Sunny Madra, and a number of core engineers joined NVIDIA; the hollowed - out Groq company and its cloud business will continue to operate.

Market interpretations of this acquisition are divided. One view is that it is a defensive acquisition. James Wang, Director of Product Marketing at Cerebras, holds this view, arguing that Groq’s microarchitecture is no magic—it has simply bet on SRAM (Static Random - Access Memory), and NVIDIA made the acquisition to avoid a potential $200 billion loss in the future.

Another view sees it as a technological and strategic expansion. LPUs can provide low - latency differentiated services in the inference era, much like Mellanox, which NVIDIA acquired several years ago and which has now become a networking business generating approximately $20 billion in annual revenue.

There is also a view that it is a move to curry favor with regulators. Chamath Palihapitiya, a friend of David Sacks, the White House AI Director, and Donald Trump Jr. are both investors in Groq.

Regardless, one more potential challenger that could have caused some trouble for NVIDIA is now out of the picture. In the second half of this year, Meta acquired Rivos; Intel once competed to acquire Groq but later shifted its focus to SambaNova. Additionally, Marvell acquired Celestial AI. Cerebras remains, planning to go public as soon as possible. The industry is accelerating its integration, indicating that this is not merely a “defensive” move but a systematic expansion and restructuring of the entire computing power ecosystem.

TPUs have transformed AI competition, shifting the focus from models to infrastructure and disrupting NVIDIA’s dominance. Ironically, the foundation of the Groq team that NVIDIA acquired was laid during their time developing Google’s first - generation TPU, adding a touch of fate to the acquisition. Jonathan Ross once designed and implemented the core elements of the first - generation TPU chip. When he left Google, he took 7 out of the 10 core members of the TPU team with him. Together, they built the LPU (Language Processing Unit) for Groq, which is claimed to be 10 times faster than NVIDIA’s GPUs for natural language processing while consuming less energy.

The magic of the LPU lies in SRAM. Unlike GPUs that use HBM (High - Bandwidth Memory) and need to frequently load data from external memory and rely on high - speed data transmission, the LPU does not have such needs. It only performs inference computations, which require much less data than model training, resulting in less data reading from external memory and lower power consumption than GPUs. It also achieves seamless connectivity between multiple TSPs, avoiding bottlenecks in GPU clusters and significantly improving scalability.

Groq emerged, challenging both NVIDIA and Google simultaneously

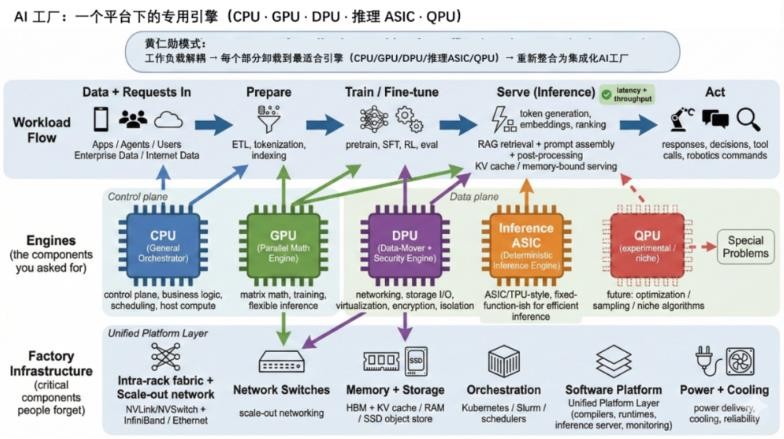

As a result, this acquisition serves as an enhancement to NVIDIA’s AI factories and an active, systematic expansion. In an internal letter, Jensen Huang stated that Groq’s technology license to NVIDIA will expand NVIDIA’s service capabilities, enabling it to optimize real - time workloads for customers across a broader range of AI inference tasks.

Inference caters to a wide variety of scenarios, each with distinct workload requirements. In agent scenarios, low latency and consistent performance are more crucial than peak throughput. In the short term, in these application scenarios, LPUs that can deliver differentiated experiences will generate higher token value compared to traditional GPUs.

This is the “dopamine economics” of tokens. A few months ago, Jonathan Ross drew an analogy with profit margins in the consumer goods industry, stating that the core variable determining profit margins is the speed at which a component acts on the human body—“every 100 - millisecond speed - up leads to an approximate 8% increase in conversion rates.”

In the longer run, NVIDIA is also likely to internalize the technology and create new markets. NVIDIA is no longer a mere GPU manufacturer; it sells software, networking solutions, and even dabbles in racks and power supplies. The AI factory is a system - level solution. Products that can expand inference scenarios, enhance service value, and reduce inference costs and latency will all become Jensen Huang’s next acquisition targets. TPUs have been gradually eroding NVIDIA’s market position by virtue of their lower total cost of ownership.

Although Jensen Huang has repeatedly claimed on earnings calls that ASICs are not a threat, he did not hesitate to act when the market believed that Google’s TPUs were starting to rewrite the AI narrative. Since the beginning of this year, NVIDIA has invested in networking technology firm Enfabrica, chip design software company Synopsys, and communication technology enterprise Nokia, among others.

AI is entering the inference era, fueling a boom in the memory super cycle. The market has long speculated that NVIDIA will soon acquire a memory - related technology company. In a sense, the acquisition of Groq aligns with this expectation.

If HBM represents “greater bandwidth,” then achieving “shorter access distances” through innovations at the SRAM level is another path the industry is exploring. Professor Kim Jung - ho, known as the father of HBM, publicly released the HBM roadmap through 2038 this year. It mentions that embedding SRAM caches will become the standard in the upcoming HBM5 phase. NVIDIA will not miss the opportunity to verify this judgment.

These trends will drive 2026 to enter the “memory super cycle”

Of course, on the other hand, the acquisition is also defensive. HBM is becoming increasingly expensive, accounting for a growing proportion of the total cost of AI computing hardware and gradually eroding NVIDIA’s profit margins. In response, NVIDIA has launched Rubin CPX to demonstrate that ultra - high memory bandwidth is not necessary at all stages. Jonathan Ross claims that his advantage over NVIDIA is that his products do not require HBM. At the very least, this acquisition serves as a structural hedge. For memory manufacturers, expanding HBM production is a capital - intensive gamble, but increased supply will drag down profit margins. In contrast, SRAM is relatively easier to manufacture and package.

A more significant impact is that every link in NVIDIA’s upstream and downstream supply chain is attempting to break free from NVIDIA’s dominance. Google’s self - developed TPUs have already challenged NVIDIA’s AI narrative. In recent years, Samsung has also been strengthening its system design capabilities. It is not only planning to develop its own GPUs but also increasing its investment in ASIC foundry services and entering the market with edge AI chips.

Prior to this acquisition, Dennis Abts, former Chief Architect of Groq, had already joined NVIDIA in advance. After leaving Groq, Thomas Sohmers, its former Director of Strategy, founded Positron, another AI chip company aiming to challenge NVIDIA. Positron is betting on the large - scale inference demand for low latency and low power consumption, while taking both the ASIC and FPGA routes. Many other Groq engineers have moved to d - Matrix, which also focuses on SRAM architecture.

With tens of billions of dollars in cash on its balance sheet, will NVIDIA continue to acquire, absorb, and turn challengers into “teammates” next year? On the other side of the Pacific, how should Chinese AI chip companies, which are still in a fragmented competitive landscape, respond to the ever - expanding NVIDIA?

|