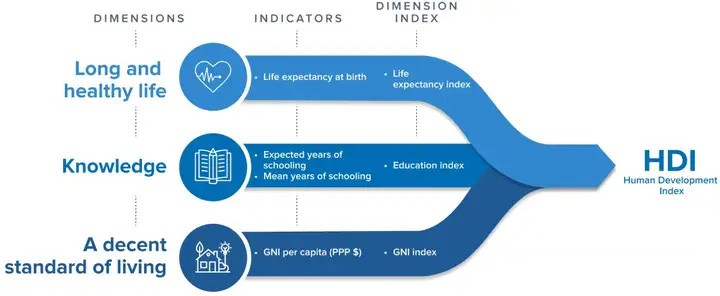

First, before discussing the Human Development Index (HDI) and its rankings, one must at least clarify the definition and calculation method of the HDI. The HDI comprises three components: life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling and expected years of schooling), and gross national income per capita. It is designed to measure key dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge, and a decent standard of living.

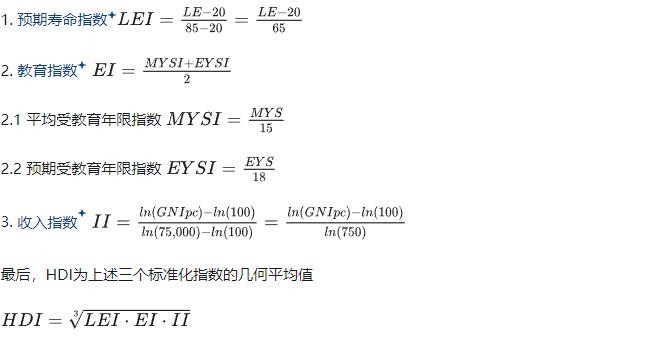

The calculation methods for each component are as follows:

Thus, given such a standardized index, I personally see no trace of any sinister “Germanic lizard-people caste-based win-theory” embedded within it. Of course, if certain “barbarology scholars” insist the index is biased, they are welcome to run their own econometric analyses—by all means, go ahead.

Now, let’s examine the countries mentioned in the question. Life expectancy is roughly similar across these nations, so its impact on rankings is negligible. As for former Warsaw Pact countries in Eastern Europe—such as Romania, Russia, and Hungary—their GNI per capita adjusted by purchasing power parity (PPP) (note: some answers mistakenly use nominal GDP per capita; please get the concepts right) is over 50% higher than that of mainland China. I don’t think this is particularly controversial. Meanwhile, countries like Armenia, Georgia, and Serbia, whose per capita income is roughly on par with China’s, benefit from an “education bonus” in the HDI—likely a legacy of the Soviet or Yugoslav education systems. Iran exemplifies this even more clearly: aside from mean years of schooling (MYS), none of its other indicators surpass those of China.

Specifically, MYS refers to the average number of years of education actually received by people aged 25 and older, based on the overall population’s educational attainment. For example, if every citizen in a country completed 15 years of education before age 25, that country’s MYS would be 15.0—not 1.0 as incorrectly stated in the original text (this appears to be a misunderstanding; MYS is measured in actual years, not normalized to 1.0). In China’s case, the relatively low MYS reflects the fact that older generations received far less education—a consequence, arguably, of the suspension of the national college entrance exam (Gaokao) during certain historical periods.

Of course, one could also argue that the “diploma mills” of the former Eastern Bloc produced worthless degrees, and thus propose excluding education entirely from the HDI—considering only life expectancy and income. Under such a revised metric, mainland China (0.852) would surpass Georgia (0.822), Iran (0.825), Armenia (0.829), Thailand (0.836), and Serbia (0.847).

Finally, let’s address Thailand—a country frequently cited in other answers. I believe Thailand is the least controversial example here. It’s right next door, offers visa-free entry to Chinese citizens, and one can easily fly over for a visit and enjoy some durian. Thailand’s HDI is only 0.001 higher than China’s—well within the margin of calculation error. If we were to treat Thailand as a Chinese province, its development level would comfortably sit among China’s mid-tier provinces. A difference of merely 0.001 is entirely plausible and not at all unreasonable. Ask yourselves honestly: are Nanning in Guangxi or Kunming in Yunnan really significantly more developed than Bangkok?

|