Andrej Karpathy, a founding member of OpenAI and an expert in deep learning and autonomous driving who previously led AI at Tesla, has emerged in recent years as a prominent voice in the AI community.

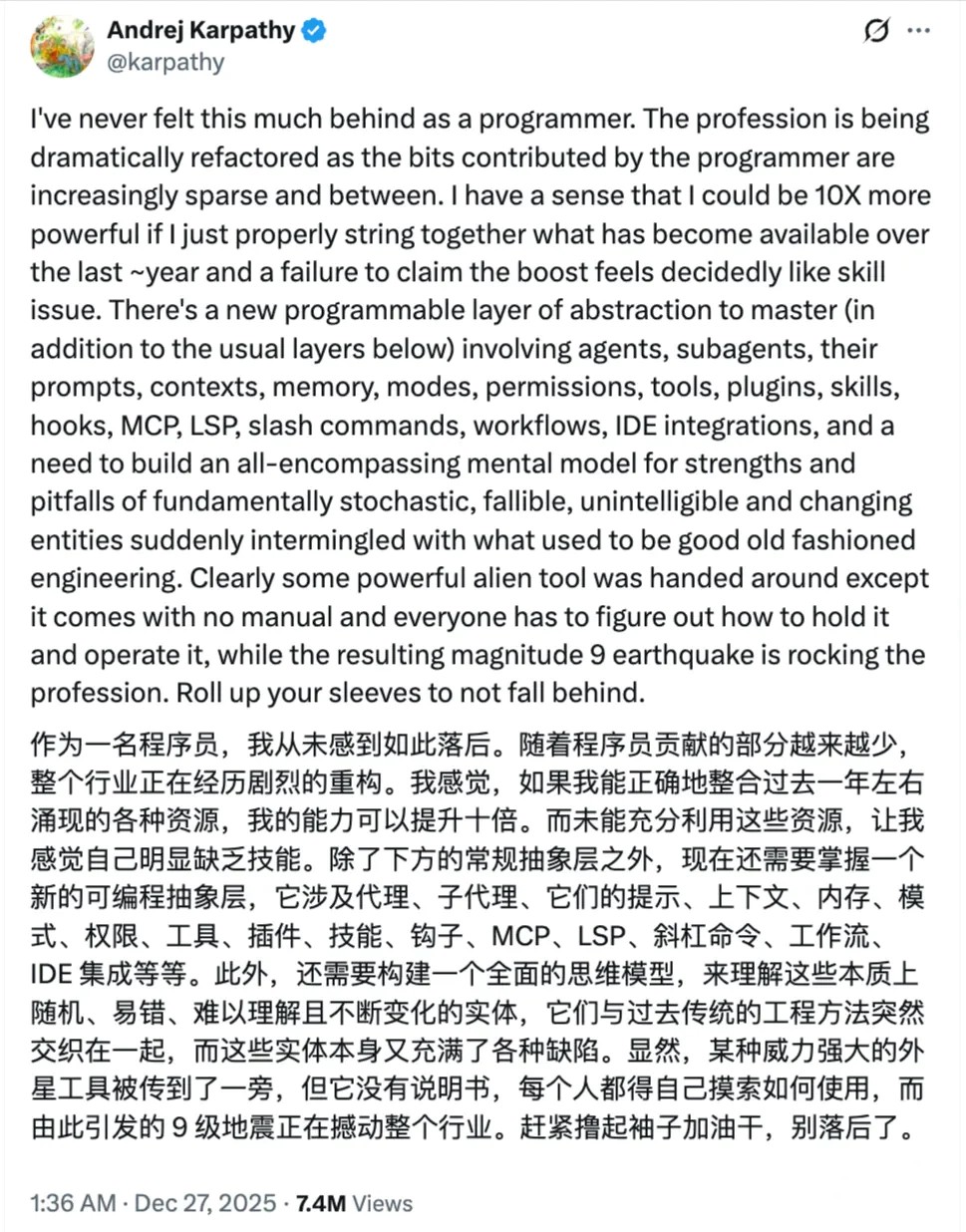

Today, he posted a tweet saying, “As a programmer, I’ve never felt so strongly that I’m falling behind. This profession is being radically reshaped… a magnitude-9 earthquake is shaking the entire industry. Roll up your sleeves and get to work—don’t get left behind.”

This tweet may have perfectly captured the collective sentiment among programmers in 2025: anxiety, excitement, and a suffocating fear of falling behind if you stop learning. Over the past year, new terms like agents, sub-agents, MCP (Model Context Protocol), workflows, and IDE integrations have flooded the discourse. Companies are simultaneously laying off staff in pursuit of AI-driven productivity while grappling with real-world costs—hallucinations, workflow breakdowns, and permission chaos.

Karpathy remarked, “It’s as if someone handed everyone a powerful alien tool—but without a manual. Everyone has to figure out how to understand and operate it on their own.”

AI certainly seems capable. 2025 was heralded as the “Year of the Agent.” So how far are we really from true “automation of everything”?

The New Yorker has just published an article by Cal Newport titled “Why A.I. Didn’t Transform Our Lives in 2025,” offering a sober—even somewhat deflating—answer. Newport’s core argument is blunt: 2025 did not witness the breakthrough of general-purpose AI agents; the industry overpromised and underdelivered.

He points out that agents shine in programming because the terminal is inherently a text-based world, perfectly suited for large language models. But once they step outside the terminal and into real-world workflows—requiring mouse clicks, webpage interactions—they become slow, prone to getting stuck, and errors compound across multi-step tasks.

Gary Marcus, a well-known AI critic, put it scathingly: “They’re just stacking one clumsy tool on top of another.” Andrej Karpathy himself stated bluntly in a prior interview that agents “just aren’t working.”

The article doesn’t reject AI—it simply reins in the hype and returns expectations to engineering reality and cognitive baselines: either rebuild the internet with robot-friendly protocols, or fix the models’ shortcomings in temporal reasoning, spatial awareness, and common sense.

Below is the full article. By the end, you might agree with Karpathy’s assessment: rather than the “Year of the Agent,” 2025 may mark the beginning of the “Decade of the Agent.”

This was supposed to be the year when autonomous agents took over mundane daily tasks. The tech industry made bold claims—but delivered far less than promised.

A year ago, Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, made a bold prediction: “We believe that in 2025, we might see the first AI agents ‘enter the labor market’ and substantially change how companies produce output.”

Weeks later, Kevin Weil, OpenAI’s Chief Product Officer, said at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January: “I think 2025 is the year we move from ChatGPT being just a super-smart thing… to ChatGPT actually doing things for you in the real world.” He gave examples like filling out online forms or booking restaurant reservations. He later added confidently: “We will absolutely get there—no doubt about it.” (OpenAI has a corporate partnership with Condé Nast, The New Yorker’s parent company.)

This wasn’t mere boasting. Chatbots respond directly to text prompts—answering questions or drafting an email. But in theory, agents can navigate the digital world autonomously, executing multi-step tasks that require interacting with other software, such as web browsers.

Consider booking a hotel: selecting dates, filtering by personal preferences, reading reviews, comparing prices and amenities across sites. Conceptually, an agent could automate all of this. The implications would be enormous.

Chatbots are convenient tools for human workers; efficient AI agents might replace them outright. Marc Benioff, CEO of Salesforce, declared that half of his company’s work is already done by AI and predicted agents would ignite a multi-trillion-dollar “digital labor revolution.”

Part of why 2025 was dubbed the “Year of the AI Agent” stems from the undeniable proficiency these tools showed in computer programming by late 2024. In May, a demo of OpenAI’s Codex agent showed a user asking it to modify his personal website: “Add a new tab next to ‘investment/tools’ called ‘food I like.’ Put —tacos—in the document.”

The chatbot swiftly executed a sequence of interrelated actions: it inspected the site’s directory structure, examined a promising file, used search commands to locate where to insert the new code, and successfully added a page themed around tacos.

As a computer scientist, I must admit: Codex handled this task more or less the way I would have. Silicon Valley took this as proof that harder tasks would soon fall too.

Yet, as 2025 draws to a close, the era of general-purpose AI agents has not arrived. In the fall of 2025, Andrej Karpathy, co-founder of OpenAI, left the company to launch an AI education initiative. He described agents as “cognitively lacking” and said plainly: “It’s just not working.”

Gary Marcus, a longtime critic of tech hype, recently wrote on his Substack: “So far, AI agents have mostly been a dud.” This gap between promise and reality matters.

Impressive chatbots and reality-bending video generators are astonishing—but alone, they cannot usher in a world where machines handle most of our activities. If leading AI companies fail to deliver broadly useful agents, they may not fulfill their promises of an “AI-driven future.” (In the AI era, what was once simplest has now become the biggest problem.)

The term “AI agent” evokes images of high-powered tech from The Matrix or Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning. In truth, agents aren’t custom-built digital brains; they’re powered by the same large language models that drive chatbots.

When you ask an agent to perform a routine task, a controller program—a straightforward application that orchestrates the agent’s actions—translates your request into a prompt for the language model: What do I want to achieve? What tools are available? What should I do first? The controller then attempts the action suggested by the model, feeds back the result, and asks: “What next?” This loop continues until the model declares the task complete.

This architecture turns out to be especially good at automating software development. Most actions needed to create or modify a program can be accomplished by typing a limited set of text commands into a terminal—commands that navigate the file system, add or update source code, and compile human-readable code into machine-executable bits.

For large language models, this is an ideal environment. “The terminal interface is text-based, and language models are fundamentally built on text,” Alex Shaw, co-creator of Terminal-Bench—a popular benchmark for evaluating coding agents—told me.

But the more general assistants envisioned by Altman require agents to leave the comfort of the terminal. Since most people complete computer tasks by pointing and clicking, an AI that truly “joins the workforce” would likely need to learn to use a mouse—an unexpectedly difficult challenge.

Why are smart people fleeing social media?

The New York Times recently reported on a wave of startups building “shadow sites”—replicas of popular web pages like United Airlines or Gmail—so AI can study how humans move cursors on these copies. In July, OpenAI released ChatGPT Agent, an early version of a browser-based robot capable of completing tasks.

But one review noted: “Even simple actions like clicking, selecting elements, or searching can take an agent several seconds—or even minutes.” In one case, the tool got stuck for nearly 15 minutes trying to select a price from a dropdown menu on a real estate website.

Another path to enhancing agents is making existing tools more AI-accessible. One open-source effort aims to develop the Model Context Protocol (MCP)—a standardized interface allowing agents to access software via text requests.

Google introduced its Agent2Agent protocol in spring 2024, envisioning a world where agents interact directly with each other. If my personal AI could instead query a specialized AI—perhaps trained by a hotel chain—to book a room on my behalf, it wouldn’t need to navigate the hotel’s website itself.

Of course, rebuilding internet infrastructure around robots takes time. (For years, developers have actively tried to block bots from crawling websites.) And even if engineers succeed in taming the mouse or redesigning interfaces, they’ll still face another challenge: the inherent weaknesses of the large language models that power agent decision-making.

In a video announcing ChatGPT Agent, Altman and OpenAI engineers demonstrated several features. At one point, it generated a map supposedly showing a tour of all 30 Major League Baseball stadiums in North America. Oddly, the route included a stop in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico.

You could dismiss this as a fluke, but for critics like Marcus, such errors reveal a deeper flaw. He told me large models lack sufficient understanding of “how things work in the real world,” making them unreliable for open-ended tasks. Even in relatively straightforward scenarios like trip planning, he said, “you still have to reason about time, you still have to reason about location”—basic human capabilities that language models struggle with. “They’re just stacking one clumsy tool on top of another,” he said.

Others warn that agents amplify errors. Chatbot users quickly learn that large models tend to hallucinate; a well-known benchmark shows that different versions of OpenAI’s cutting-edge GPT-5 model still exhibit hallucination rates of around 10%.

For agents executing multi-step tasks, this semi-regular drifting can be catastrophic: a single misstep can derail the entire operation. In spring 2024, Business Insider ran a headline warning: “Don’t Get Too Excited About AI Agents. They Make a Lot of Mistakes.”

To better understand how a large language model might go off track, I asked ChatGPT to explain the plan it would follow if it were driving a hotel-booking agent. It outlined an 18-step sequence with substeps: select a booking site, apply filters, enter credit card info, send me a summary, etc.

I was impressed by how granularly the model broke down the task. (It’s easy to underestimate how many tiny actions a common task actually involves—until you see them listed one by one.) But I could also see exactly where our hypothetical agent might fail.

For example, in substep 4.4, it proposed ranking rooms using a formula: α*(location score) + β*(rating score) ? γ*(price penalty) + δ*(loyalty bonus). While this type of approach is correct in principle, the model’s handling of details was unsettlingly vague.

How would it calculate the penalty and bonus values? How would it choose the weights (represented by Greek letters) to balance them? Humans would likely tune these manually through trial, error, and common sense—but who knows what a language model would do on its own. And small errors could be disastrous: overemphasizing “price penalty” might land you in one of the worst hotels in town.

A few weeks ago, Altman announced in an internal memo that developing AI agents is just one of many projects at OpenAI, and the company would de-emphasize this direction to focus on improving its core chatbot product. Just a year ago, leaders like Altman spoke as if we’d already gone over a technological cliff edge, tumbling chaotically toward an army of automated labor.

Now, that fervor seems premature. Recently, to recalibrate my own expectations about AI, I’ve been thinking about a podcast interview from October—with OpenAI co-founder Karpathy. Interviewer Dwarkesh Patel asked him why the “Year of the Agent” hadn’t materialized.

“I think there’s been some over-prediction in the industry,” Karpathy replied. “In my view, a more accurate framing is: this is the ‘Decade of the Agent.’”

|